Everything you need to know about the GTA’s recent explosion in gun violence

Jaron Goldin SCIENCE & TECH EDITOR

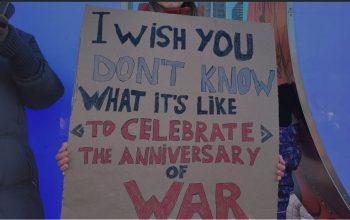

Photo: TORONTO STAR

Gun violence in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) has been a particularly relevant topic recently. There exists a public panic, fuelled by a number of high-profile shootings. The Toronto Police recorded 228 shooting incidents since January 1st to the end of July, with 308 victims of gun violence, and 29 people fatally wounded. There has been a 10% increase in the number of shootings since 2016. That does not indicate a great surge or spike in gun violence. That may not sound as much as one might have expected, with gun violence being the big topic this year. It feels like almost every day a new murder or shooting in any one of the boroughs in the GTA is being broadcasted. By July, it was confirmed that our homicide rate was slightly higher than the historically higher rate in New York City. But New York’s rate has been on the decline, and the homicide rate is still higher in cities such as Winnipeg and Chicago. This small fact has propagated in the media, certainly stirring the moral panic.

What are the facts? Last year, Toronto had 205 shootings and 299 victims of gun-related violence. There were 208 shootings by the end of July 2016. Shooting deaths in 2018 are up 70% from last year, but only 16% higher than 2016. This is why we are seeing so many news stories about it this year.

The location of shootings has changed this year. Shootings in the Kensington, University, and Richmond and Spadina neighbourhoods increased by over 250% compared to 2016. The number of shootings in neighbourhoods like Rexdale, Jane and Finch, and Lawrence Heights, which tend to experience higher rates of gun violence, have declined by a combined 40% since 2016.

Earlier in the year, the government said gang-related homicides have almost doubled since 2013 in all major Canadian cities. Activist Louis March says guns are more widely available than ever before — “There are more guns out there than there are jobs,” he said — and the calibre of the weapons has increased, from smaller handguns to semi-automatics.

“The people using the guns are young kids, teenagers. The brazenness of the shootings, in public spaces, that has changed — in a playground, in a public shopping mall; we didn’t used to see that,” March stated.

While March said it is good that the city is making movement toward progress, he said Toronto is mostly doing so because gun violence has reached areas that aren’t often affected, such as Queen Street and Danforth Avenue. “[When gun violence] was in certain neighbourhoods where there’s poverty, unemployment, lack of education, lack of supports, it didn’t seem to concern them. But now that it’s in the public spaces … they’re concerned,” March said. “And that is scary because they’re deciding which lives are important and which are not.”

Activist concern

Black community activists have condemned Mayor John Tory for using words like “thugs” to describe the perpetrators of gun violence in Toronto. Idil Abdillahi, an assistant professor at Ryerson University’s School of Social Work, said that dehumanising language has very real effects on all black residents of Toronto.

“How do you reconcile identifying us as non-human, while also then saying that we’re going to put money into social programmes?” she asked.

Ontario’s Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services, Michael Tibollo, and City Councillor Giorgio Mammoliti wore bulletproof vests to visit Jane and Finch, provoking people to accuse the politicians of fueling the misconception that the neighbourhood is ripe with danger. “Every time we deem black people as dangerous, we need to understand there are real life outcomes and consequences, and those … are death: death as in actual death, and death as in social and political death and isolation,” Abdillahi said.

Abdillahi was among a group of activists, scholars, and community members who signed an open letter that urged the city to treat gun violence as a public health issue.

“Research and common-sense show that an increased militarisation of police does not curb gun violence and certainly is not focused on prevention,” the letter reads.

“We demand that the millions approved for militaristic interventions in these neighbourhoods go to community initiatives to provide affordable housing, jobs, and social and health services.”

What is being done?

City Council has approved $8 million for use in addressing gun violence. $7.4 million of it is for enforcement and surveillance activity, while $1 million is for investment in communities aimed at tackling the root causes of violence.

Four million dollars have also been invested in ShotSpotter technologies, which have been criticized as a means of increasing surveillance of communities often targeted by the criminal justice system. The technology — a network of microphones that can be affixed to buildings, lamp-posts and other structures — is meant to help rapidly recognise and locate gunshots, and then transmit that information to first responders, including police. It is unclear whether it is effective in reducing gun crime. According to a 2016 investigation by Reveal, a project from the U.S.-based Center for Investigative Reporting, of the more than 3,000 ShotSpotter alerts sent out over a two-and-a-half-year period in San Francisco, only two arrests were made, and only one of those was related to a gun.

More police than usual have been deployed to patrol areas which the city deems as “high risk.” Tory has renewed calls for tougher firearm restrictions in the wake of the Danforth shooting. “Why does anyone in this city need to have a gun at all?” Tory questioned.

The City Council has passed a series of measures meant to curb gun violence, including a request for the federal and provincial governments to ban handgun and ammunition sales in Toronto. But, many community activists believe the solution lies in community-led initiatives and socioeconomic opportunities, as well as in ending policies that have led to discrimination.

This is not the first time Toronto has experienced a public outcry and attempted to counter the problem. After a surge in gun-related murders in 2005, known as the “Summer of the Gun,” Toronto put in place a police program called the Toronto Anti-Violence Intervention Strategy (TAVIS), aiming to counter gun violence by deploying more officers in areas with high levels of it.

Critics said the controversial programme led to racial profiling, with a Toronto Police practice known as “carding,” allowing officers to stop and check people’s IDs without needing to have a reason, and the criminalisation of black communities.

In 2012, shootings at the Eaton Centre, a multi-floor, downtown shopping mall, and at a block party in Scarborough, an eastern suburb of Toronto, also led to a flurry of promises to crack down on gang violence. Toronto’s then-mayor, the late Rob Ford, vowed to boost police funding and launch a “war on gangs.” He also rejected calls to bolster community programmes, calling them “hug a thug” initiatives that don’t produce results.

While TAVIS was cancelled in 2016 after the provincial government slashed its funding amid widespread criticism, current Ontario Premier Doug Ford has hinted at bringing it back.

Community Opinion: How Important?

The government looks like it is looking to change things by enforcement, laws, and protection. But how successful is that really?

Beverly Bain, a professor of Women and Gender Studies at the University of Toronto’s Mississauga campus, says she has seen over-policing in black communities in Toronto for over 40 years. She said black communities are not the sources of violence in the city, but they are recipients of it, often through heavy-handed police tactics and other policies.

“What goes on in the black community is a response to the violence that it experiences, and the responses to the kinds of policing and the kinds of state economic and political strategies that bear down on this community, forcing them to live in untenable conditions,” Bain says. “It has to be approaches that are less about policing, and more about creating socioeconomic policies.”

“[The solution] cannot be putting more police officers into these communities. It cannot be about arming our police officers. It cannot be about more surveillance technologies, and it cannot be about TAVIS.”

Louis March, the activist mentioned earlier, agrees with Bain. He believes that the local programs working to address gun violence in communities need to be funded better and grown. Instead of arming police officers and putting more on patrol, the funding from City Council should go to underlying, base causes of violence in our neighbourhoods, such as poverty, oppression, neglect, and social exclusion.

March believes the government is not addressing the problem in a meaningful way at all.

Should Canada completely ban guns?

The darkest part of this year’s violent gun activity is the mass shooting at Danforth Avenue that took place on July 22. 29-year-old Faisal Hussain opened fire with a handgun in Toronto’s Greektown, killing two young girls — 18-year-old Reese Fallon and 10-year-old Julianna Kozis — while injuring another 13. Tory stated after the shooting that the city has a gun problem.

“You’ve heard me ask the question of why anybody would need to buy 10 or 20 guns, which they can lawfully do under the present laws. And that leads to another question we need to discuss: Why does anyone in this city need to have a gun at all?” Mayor Tory said.

In Canada, we have an abundance of weapons. A 2017 report from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s (RCMP) Commissioner of Firearms shows 839,295 restricted and prohibited guns across Canada. That is almost double the amount from 2005, which was 480,000. Nationwide, in 2017, there were 2,734 firearm-related violent offences, compared to 2,534 in 2016.

The handgun debate in Canada has been going on for more than 20 years, and more than 60% of Canadians support totally banning firearms. Over the sea, our friends in the United Kingdom had only 27 gun murders for its population of 60,000,000 people last year. This is due to strict gun laws that have successfully minimalized gun violence since the 1996 Dunblane school massacre in Scotland. Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale has said that, while Ottawa is prepared to consider a proposal to ban handguns, such changes would be complex and require a “significant remodeling of the Criminal Code.” Using countries such as the U.K. and Australia as examples, Canada should start reforming our laws and restrictions, eventually to minimize gun violence as much as possible.

What is interesting is that Jordan Donich, a defence lawyer in Toronto, says banning handguns would not influence firearms-related homicides as most guns used in murders are smuggled here illegally. Agreeing with activists mentioned earlier, she thinks policymakers should be looking at the reasons why young men pick up a gun in the first place.

[JS1]Need full name on first reference