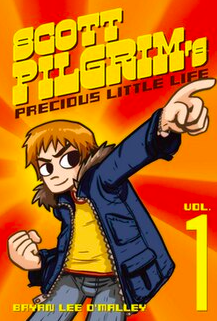

Photo Credit: Bryan Lee O’Malley

Or how, sometimes, spinoffs might not be so bad after all

Jacqueline Cho, Contributor

This review contains major spoilers for Scott Pilgrim Takes Off (2023).

I am sick of reboots, unnecessary sequels, and spinoffs.

This is not an unpopular opinion, but I wouldn’t be the first to argue that we need to let stories die once they reach their natural end. Sometimes, we don’t need to know what happens next, actually. Given how inundated the market has been with remakes or adaptations with nothing new to offer, we need to recognize these stories for what they are: cheap cash grabs.

Scott Pilgrim Takes Off could have very well taken that route. The nostalgia bait alone from gaining borderline the entire original live action movie cast back would have been enough for everyone involved to make a nice profit before tucking this franchise back into the grave.

Instead, the show takes a daring leap by killing off Scott Pilgrim within the first episode.

For the record, I have been a fan of the 2010 live action movie for years. While I thought the comic was far better, I respected the strength and charm of the film as an adaptation (also because the comic itself had not concluded by the time the movie was produced). One of Scott Pilgrim’s strengths has been the advantages it takes from the medium it is produced in. The comics tell a different story from the movie because it is a different story. Starting the first episode off with killing your protagonist is a bold one, and one that continues this tradition. This is not just an adaptation of the comic material or a cheap continuation of the movie, but an entirely new narrative. Scott Pilgrim Takes Off isn’t about Scott at all: it’s about Ramona. Rather than a narrative that would have retold the tale of Pilgrim’s fights to date Ramona, Ramona actually makes amends with her exes, showing prolonged character development and presence in a way that was never quite portrayed in the 2010 film. Ramona isn’t the object of Scott’s affections; she’s the very subject of the narrative. While Scott comes back, this choice, along with the entire decision to make a wholly new take on Scott’s story (indeed, turning it into Ramona’s story) allows for a new story to be told while still being respectful of the source material.

Additionally, I would be remiss to not consider that a newer adaptation allows some of the initial sins of the movie and comics to be amended. After all, the world has deeply changed since 2004 when the comic was first published, and in 2010 when the movie was released. Queer subjects, specifically Roxy and Ramona’s former relationship, are handled with deeper care rather than reducing bisexuality to a cheap experiment. Furthermore, the choice to center the narrative around Ramona gave her agency in a way that the 2004 comic and 2010 film neglected. Given that Ramona Flowers was the epitome of the manic pixie dream girl trope, giving her agency and centering the narrative around her allowed the animated series skillfully to sidestep any pitfalls into the initial critiques of the misogynistic trope it previously portrayed. While I am tempted to be cynical and say this is a way to dismiss criticism of misogyny and homophobia in the initial material entirely, the deliberate choice to recenter the narrative around Ramona allows O’Malley not just to add to the canon but enhance it.

At the beginning of this review, I said we need to let stories die. When they’ve reached their natural end, we need to learn how to let go. And while I stand by this sentiment, if every reboot or spinoff treated their source material and adaptation as a way to add to their overarching narrative, maybe some stuff would be worth coming back to.