Gentrification and Revitalization in Toronto’s Best Known Neighbourhoods

Liza Mironova – CONTRIBUTOR

A Native performer dripping in sweat whilst playing a harmonious tune on the flute, dancers decorated in exotic costumes handing out flyers, a crowd of people bouncing to the simultaneous beat of drums and Latin music — was this a dream?

Sundays are unusually quiet days in Toronto if compared to New York or Moscow. People here, tend to spend the day recovering from a long weekend of partying, take the day off to see their families in the suburbs, or do what I was doing — catch up on endless reading for school.

To mix it up, I decided to take a break from Robarts and explore coffee shops in Kensington Market. I made my way down Spadina to find the streets blocked off to cars. A distinct smell curled around the corner from what seemed to be Augusta Avenue and the scene was more chaotic than usual. I could not miss the date with my Netherlandish Renaissance Art readings, so I pushed my way through the crowd.

A lingering spicy aroma created a cloud around a burning grill covered in pork and cheese papusas — this is where I had to stop before reaching Eative (one of my favorite study spots in town), and figure out what in the world was going on.

What I thought to be a dream, was actually a case of Kensington Pedestrian Sundays. Organized on the last day of each month from May through October, Pedestrian Sundays offer Torontonians a great way to interact with the Kensington community. Kids run and play on the streets, small food joints have booths set up on the streets, and the streets begin to resemble a carnival inspired by different regions of the world.

I soon discovered that this concoction of energy in Kensington has been permeating Toronto’s streets for nearly a decade. According to research done by Heather McLean and Barbara Rahder of York University, Kensington Pedestrian Sundays were an initiative that began in 2004 as a way to protest car culture and the “influx of condominium development.” It sought to promote community interaction and culture.

Hip, entertaining, and dynamic, are words we often associate with Kensington Market, so it should come to no surprise that there is a crazy and fun event like Pedestrian Sunday. It is the iconic, hipster neighborhood which is best known for its selection of vegan restaurants (urban Herbivore), quirky underground bars (Cold Tea), and mouthwatering dessert cafes (Millie Creperie). It all falls into place.

Queen Street West could very much rival Kensington for the title of “most iconic and hipster neighborhood,” with its plethora of clubs, graffiti, and small coffee shops with the finest roast coffees of South America. It accommodates one of the largest selections of boutique stores in Toronto — anything from large brands like Anthropologie to smaller ones like Canon Blanc.

Yet, the two neighborhoods looked totally different just 30 years ago.

All throughout history, Kensington was home to the working class immigrants. Starting in the early 19th century, the area saw an influx of Jewish settlers from Eastern Europe. These settlers a close-knit community, opening up a variety of stores and creating the original ‘market place.’ It was not unusual to see newcomers buying out whole structures, as housing was very affordable. Stores would take up the ground level of the home, and the upper levels were used as living space. Kosher meats and idiosyncratic European products were in demand, so it made sense for many families to produce and sell outside the home.

The ‘market place’ trend continued, but the cultural structure itself underwent a historically significant transformation, of which we can still see fragments of today. In the 1960s, that very same area – west of Spadina, between Dundas and College — turned into a bustling amalgam of ethnicities. Portuguese, Italians, Chinese, Latin Americans, Afro-Caribbean. You name it – every mix of foreign tradition was there. Each new culture flavor added to the architecture and aura of the neighborhood and shaped the infrastructures that are still in place today.

The archives of Queen Street West on the other hand, do not invoke the same sense of profound cultural heritage and positivity as the former neighborhood’s chronicles do. In 1850, one of the most scandalous institutions of the time opened its doors — Provincial Lunatic Asylum at 999 Queen Street West. Joseph Workman, who stepped in as medical director in 1853, and the institution itself, came under public scrutiny for being corrupt and treating its patients poorly.

About a century later in the early 1960s, the neighborhood saw its greatest decline. It was blocked off from the water by the construction of the Gardiner Expressway and because of a better system of transportation, industrial manufacturing was moved to the suburbs. Warehouses were abandoned and the area came to be associated with drugs, crime, and prostitution.

Here arises the main question: how did two undeveloped, more or less isolate and poor neighborhoods become hipster and so popular in such a short period of time?

The answer is: because of artists.

Before I go onto explaining how artists made the ripple in neighborhood culture and helped create positive perceptions of Queen and Kensington, there are two terms we need to define: gentrification and revitalization.

Gentrification is the process of reinvestment in a disadvantaged area often related to an increase in property prices. It can bring improvements such as better amenities and services, but can also have negative effects as it displaces people and smaller businesses in favor of the wealthy and big name brands. Often times, it is related to white residents replacing the middle or working class. Revitalization indeed, is quite a similar to the former process, but it adopts more of a community centered approach. More businesses open with the help of the current inhabitants, but people are not displaced as frequently.

Interestingly enough, Queen and Kensington are examples of gentrification and revitalization, respectively. Urban development research curated by Carl Grodach explains that “fine arts activities are more likely associated with… Revitalization, commercial arts industries are strongly associated with gentrification.” To visualize this, we need to take a look at our examples.

As I mentioned before, after the departure of manufacturing industries from Queen Street West, many of the warehouses were left abandoned. Because of safety concerns, they could not be converted into living areas, but they most definitely could be used as studio space. Rent was cheap so slowly but surely, artist started moving in. In 1995, Artscape created 22 brand new studios where artists could live and collaborate on projects. Some bought out their own spaces, and the area became home to some of the most important players of the art world.

This created a sort of domino effect: Gallery 1313 opened shortly after, followed by Edward Day Gallery, Katherin Mulherin Contemporary Arts Projects, and more recently Birch Contemporary and Georgia Scherman Projects. Queen Street West became home to an institutional and commercial art world.

Concurrently, small bars and local restaurants were closed in favor of chain food giants and swanky pinnacles of fine dining. In addition, many of the older buildings were sold and projects to build expensive new condos registered with the government. Gentrification of Queen Street West caused by institutionalized art had a direct effect on huge improvement of the area and its fashionable ambience today.

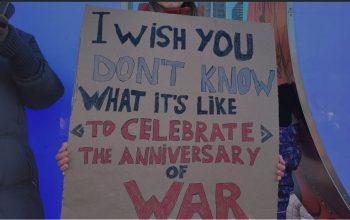

Kensington Market, which was to a lesser degree in need of reparations, took matters into it own hands when it came to art. The community saw what had happened to Queen Street West and was (rightfully) afraid that everyone would be put out of business if they let developers in. The people founded an organization entitled PS Kensington in 2002 with the aims of promoting art and culture in the neighborhood and to oppose redevelopment that would destroy the distinctive character of the area. It established the Kensington Pedestrian Sundays which allowed artists to showcase their works.

The Pedestrian Sunday that I stumbled upon had an abundance of different art media on display. There was a Kensington Market Art Fair displaying handmade jewelry, abstract painting, and mixed media works. There were Native performers, there were jazz bands. There was less “money circulation” but the individuality of each artist was preserved and absolutely no institutional presence — more fine art/arts and crafts per se.

Kensington hosts jazz festivals, concerts, and performances that encourage cultural celebration. Revitalization is at play with the new cafes and restaurants opening up, but because of the efforts of the people to keep out Walmart and Nike stores, original qualities of the neighborhood are still preserved.

Art is an important part of our development and it is very interesting how drastically it can change neighborhoods of one city. Being aware of how it effects different communities and the positive and negative aspects of gentrification and revitalization is important to preserving the heritage and individuality of the people.