The paradoxical role that fear plays in our lives

Chiara Brum Bozzi CONTRIBUTOR

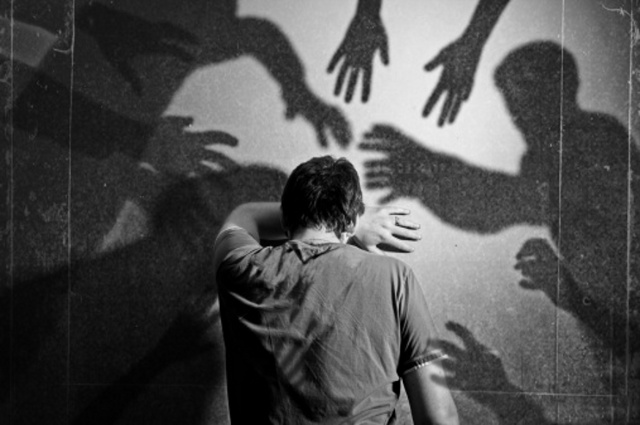

In light of the New Year, the prospect of a daunting new semester, and encroaching final marks, I deem it appropriate to discuss the crippling concept of fear of our academic and personal choices. Fear, I find, lurks ominously in many a heart of University of St. Michael’s College (USMC) students who are pursuing liberal arts majors. Often referred to as “knowledge sought for its own sake,” the lessons we learn as students in Arts and Science are often seen as lacking in practical use. While there is some truth in the thought that a degree in engineering or computer science may have more reliable and practical opportunities, to dismiss the value of the studies of thousands of students studying literature and social sciences as non-essential components of society is extremely reductive and, moreover, untrue. Take it from me: my mother, a St. Michael’s alumni, achieved a B.A. in Christianity and Culture at USMC, a Master’s in Theology at the Toronto School of Theology (TST), and is now the Senior Citizenship Judge of Canada. Now, despite my pride, I mention this as a counterpoint to those who insist (and those who believe) that the intrepid souls who choose liberal arts degrees are condemned to live a life without practicality or even meaning.

When you are afraid, dear reader, it may be because you feel as though you still have something to lose. When you have failed, hit rock bottom, and then fallen through the trap door to discover the true rock bottom, you will come to realize that doing anything, no matter how minuscule of an accomplishment, is a step toward growth. I personally characterize rock bottom as firm ground. It is a foundation that can only be built upon; it is a springboard to a higher plane. Any future acquisition of achievement, or even failure, is knowledge and potential to cobble into your arsenal. Even if you have failed, that in itself is knowledge that you have used — if only by process of elimination — and have discovered what the answer is not.

Those who do come around to making goals and seeking the right path for themselves often attempt to do so through New Year’s resolutions. The problem with New Year’s resolutions (aside from the fact that they romanticize the passing of one minute as a catalyst to incite profound change within a person without considering the pain, suffering, and effort it takes to accomplish something) is that it is goal-setting confined to the beginning-of-the-year enthusiasm that dissipates within a few hours. These resolutions enforce the same “I’ll start tomorrow,” mentality, a glorified procrastination that pushes resolution to the outer reaches of consciousness. Thwarted resolutions suggest that improvement can only occur within a certain window and that the failure to uphold that goal within the first two weeks is indicative of one’s inability to ever accomplish anything. The absurdity is laughable.

This is an interesting observation with respect to the human condition — we almost always jump at the effects of something, such as hard work, and often fail to get down to the root, the foundation, the cause. For instance, when we watch Michael Phelps winning the gold for freestyle or the butterfly stroke, we focus on the glory, the fame, the accolades, the joy, and the accomplishment only in terms of itself. What we so often miss is the arduous hard work it took to get there: the early morning risings, the hours of swimming, the treatments and daily regimen, the work, the failures, and the fear. Now I must admit that someone who races a scientifically accurate simulated shark is probably predisposed to accomplishment and suspiciously immune to failure, but I digress. The point is, our envy is rooted in success, but no one can envy the soreness, the injuries, the mental defeat, and the demanding lifestyle.

To combat this misplaced envy, I offer my own dogma: a life led well is one that acknowledges the necessity and inevitability of pain and suffering in the development of the mere possibility of success. I liken this to the great incentive to get out of bed in the morning to make that mind-numbing 8 a.m. lecture. What I mean by this is that there is no guarantee that the efforts we make will lead directly to the big ‘capital S’ Success we all desire. Acknowledging this inevitable failure and suffering is the best tactic to combat fear and to receive liberation from our own impossible standards. We cannot have control of the world, but we can control the way we navigate it: through choosing to continue in spite of the harsh reality of abject failure.

The Basilian Fathers, the founders of St. Michael’s College, maintained the logos that reads “teach me goodness, discipline, and knowledge.” To be taught is to recognize that none of us, a priori, are accomplished, nor are we exempt from failure even if we are a 28-time medal-winning Olympic swimmer. The thing about success is that it is entirely contingent upon and duly proportionate to the effort you put in the striving to achieve greatness. Now, this is not to discredit goals or resolutions at all. By all means, set goals — realistic ones, if I might add — but do not expect to achieve them within the first two weeks of the semester. Having faith and exercising your will is something we are tasked with every day. Success may be defined as taking a leap by way of making choices informed by our faith, our knowledge, our reason, and our logos.

In the words of Epictetus, “It is impossible for a man to learn what he thinks he already knows.” This openness to thought and learning is a necessary prerequisite to the act of learning in the first place. It is what allows us, Catholics and non-Catholics alike, to exercise an act of the good, recognize the true, and appreciate the beautiful. The Jesuit poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, himself said that “the world is charged with the grandeur of God,” and so we must recognize, appreciate, and inquire into it by exercising our will in the face of fear even if, just as we leap into hope, we recognize failure and fear within our academic and personal lives alike.