Announcement comes on the heels of OHRC letter, backlash

Aaron Panciera NEWS EDITOR

Bardia Besharat ASSOCIATE NEWS EDITOR

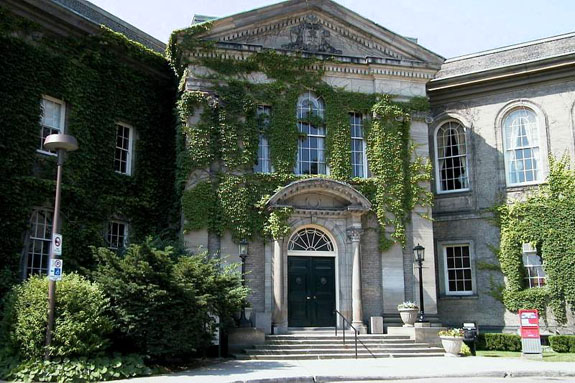

Photo: Simcoe Hall (the University of Toronto).

On January 30, 2018, the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU) and the Students for Barrier-free Access (SBA) held a panel discussion about the recent reintroduction of the proposed Mandatory Leave of Absence Policy. The policy was set to introduce a code-of-conduct–esque approach toward students with mental illness who exhibit behaviour that reaches the “threshold for intervention,” and was pulled from voting for the current semester due to student backlash and the request of the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC).

The idea for this policy was first proposed in the “Annual Report of the Office of the Ombudsperson” for 2014–15. This policy is intended to target only students who exhibit these behaviours because of mental health issues. Similar behaviour with no evidence of poor mental health could fall under other university policies unrelated to the one being proposed.

Policy Overview

“The policy is designed to be used in exceptional circumstances, and even then, only with very significant procedural safeguards for students and a rigorous approach to exploring accommodations and supportive resources,” Vice-Provost, Students, Sandy Welsh explained on the University of Toronto (U of T) website. “We need a policy that allows us to provide support for a student going through a serious episode involving a mental health or other similar issue.”

This policy is proposed with the overarching guiding principles that all students have the right to pursue their academic aspirations and that all students have the right to institutional support. The primary aspect of this policy, the actual leave of absence, is meant to be a last resort.

While this policy is not meant to be punitive in nature, if a student is subject to this mandatory leave they will not have the right to reject the decision. Instead, the student in question would have to appeal the decision to implement this policy with the University Tribunal’s Discipline Appeals Board.

However, many steps would have to be taken to reach the decision to invoke the Mandatory Leave of Absence Policy. This process would start with the student’s dean, who would request that the policy be invoked based on the student’s behaviour and concern for their well-being. From there, the student’s “case” would go to the Vice-Provost’s office, in which the student’s case manager and support team would make a decision with the Office of the Vice-Provost. At this point, a medical professional may be contacted, but this is not a requirement of the policy.

However, after a decision has been reached regarding a leave of absence, there is little in the way of guidelines for a student’s return.

“Each student would have a return-to-studies plan stating the expectations that would need to be in place to return to their program,” Welsh said. “Usually this would involve providing documentation from a health-care professional demonstrating they are well and able to engage in the essential academic activities of their particular program.”

Student Backlash

Student backlash is a major factor affecting voting on the Mandatory Leave of Absence Policy. This caused the policy to be pulled from voting during the fall 2017 voting period and again during the winter 2018 period. Even though these were massive victories for the student body, Welsh does not seem to want to scrap the policy entirely. This attitude toward the policy has sparked students to voice their opinions on not only the policy itself but the University of Toronto’s Accessibility Services as a whole.

A major concern with the Accessibility Services at U of T is the student’s burden of proof. Students are required to provide proof for their mental illness and during the panel, students expressed their opinions and feelings on the issue. The panelists discussed the arduous and difficult process of obtaining Accessibility Services and the ridiculous amounts of money and time involved with providing proof of an illness many students have had all their lives. Additionally, another major concern students voiced during the panel was the absurd wait times at the Health and Wellness Centre due to the lack of staff.

Student resentment toward the university’s Accessibility Services was only part of the SBA’s general concerns surrounding the new policy. Students on the panel, as well as within the student body, voiced concerns surrounding the nature of the policy, claiming it was more of a punishment for students rather than a solution to help those who truly need it. The panel discussed the university’s tendency to not want to help students who do not fit into the norm and require additional help, saying, “It will be affecting marginalized students disproportionately more.” They discussed the general inefficiency of the appeal process and the detrimental effects it can have on a student’s education as it may take months to have a suspension rescinded.

Withdrawal from Consideration

The proposed Mandatory Leave of Absence Policy will not be voted on this semester, per the request of OHRC Chief Commissioner Renu Mandhane.

“The OHRC is concerned that the treatment of students contemplated in the policy may result in discrimination on the basis of mental health disability contrary to the Human Rights Code,” Mandhane wrote in a letter to the university. “Given our ongoing concerns, we recommend that the policy not be approved in its current form.”

The absence of a medical professional during the process, the unclear nature of the timeline of the absence, and the lack of responsibility the policy gives U of T toward students who pose a risk to themselves were all issues raised in the OHRC’s letter.

While the policy will not be voted on this semester, that does not mean the university is abandoning the policy entirely. The policy can still be amended and put to a vote at a later date.