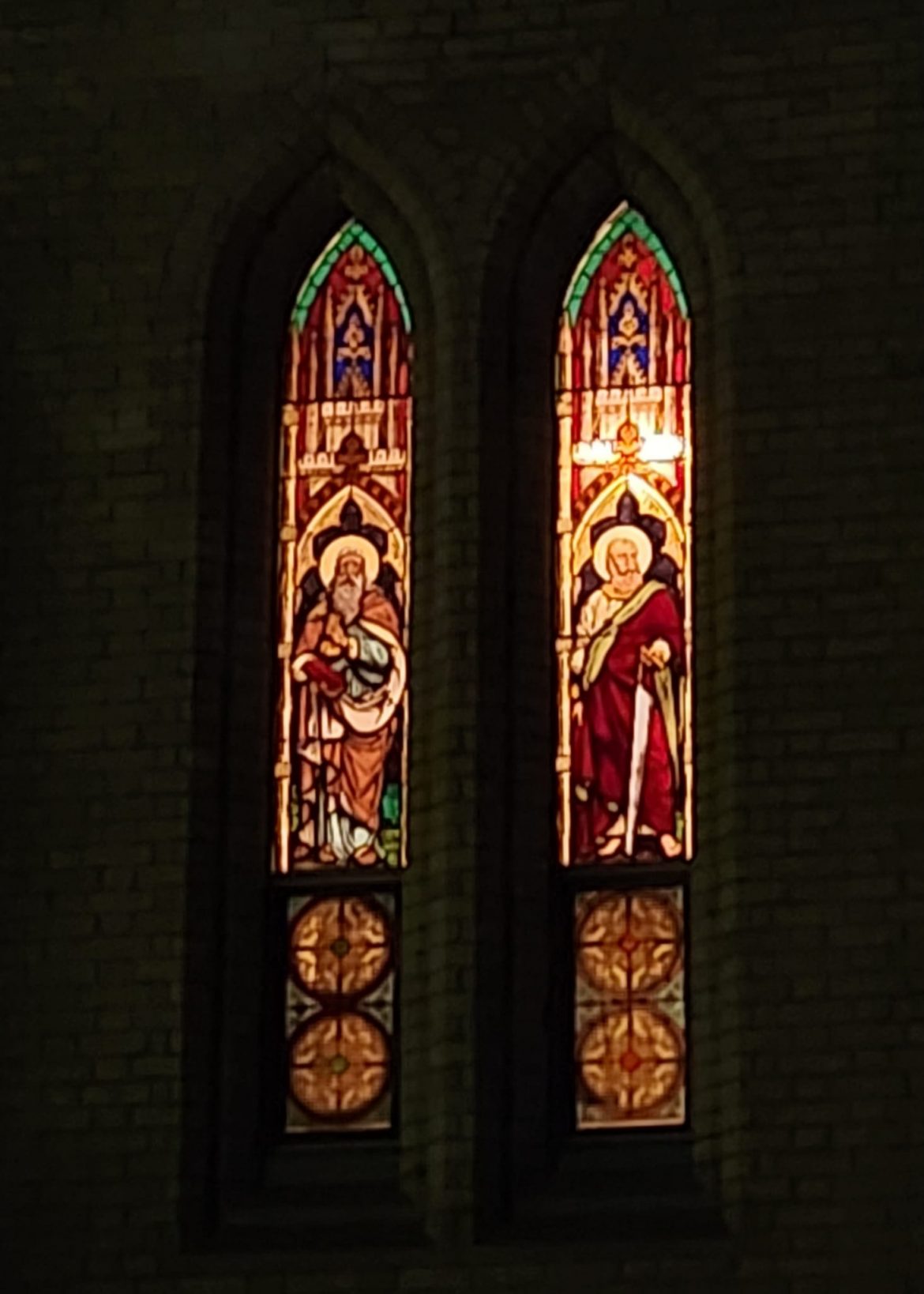

Photo Credit: Emily Tung

The necessity of the sign of peace

Para Babuharan, Logos Editor

In the Mass, after the Lord’s Prayer and before the invitation to Communion, there is a moment that seems to interrupt the sacrality of the ritual: the offering of peace. This is the moment within the rite of peace when the deacon or priest says, “Let us offer each other the sign of peace.” The original Latin is “Offerte vobis pacem,” literally, “Offer one another the peace.”

Immediately following the rite of peace is the breaking of the bread, when a piece of the host is put into the chalice. The body and blood of Christ, consecrated separately in signification of his death, are now united, signifying his resurrection. This gives the rite of peace a distinctively paschal meaning, relating back to the gospel accounts of the risen Christ saying to his disciples, “Peace be with you,” and insufflating the Holy Spirit on them.

In the words of René Girard: “Jesus distinguishes two types of peace. The first is the peace that he offers to humanity. No matter how simple its rules, it ‘surpasses human understanding’ because the only peace human beings know is the truce based on scapegoats. This is ‘the peace such as the world gives.’” The peace that we offer one another at Mass is the peace given by Christ, mystically present in the sacrament of the altar.

In the sign of peace, The General Instruction of the Roman Missal states, “the faithful express to each other their ecclesial communion and mutual charity before communicating in the Sacrament.”

Ever since the pandemic, many Catholics have stopped extending physical touch to their brothers and sisters at the sign of peace. But the contactless alternatives — a nod, a wave, or even a sixties peace sign — are sorely deficient as sincere expressions of charity.

The faithful must greet one another as family members greet each other because, in the partaking of the one body of Christ, the ecclesial family of faith is actualized. This is why only offering the peace to one’s natural relations is inimical to the universality of Christian fraternity. At the same time, Christian love involves a concrete encounter with one’s neighbour, so a hasty, impersonal signal of peace is insufficient.

Michael P. Foley, in his Antiphon article “The Whence and Whither of the Kiss of Peace in the Roman Rite,” argues for a consecrated gesture of peace that conveys the profound theological meaning of the peace that is offered. If we cannot make a familial gesture of peace like a kiss or an embrace, we must at least shake hands with those proximate to us.

Giving and receiving the sign of peace must involve some vulnerability if it is to be a true sign of the peace Christ has given us. As Andrew Bennett writes in The Catholic Register, “If we cannot touch our fellow Catholics at Mass, then how do we touch the homeless, the destitute, the poor, the sick and all those God places in our midst? If we cannot bring ourselves to offer a sincere sign of Christ’s peace, how dare we presume to touch His Most Precious and Life-Giving Body and Blood?”