Photo Credit: Samantha Hamilton, Photos Editor

Three book reviews, one writer

Julliana Santos, Arts Editor

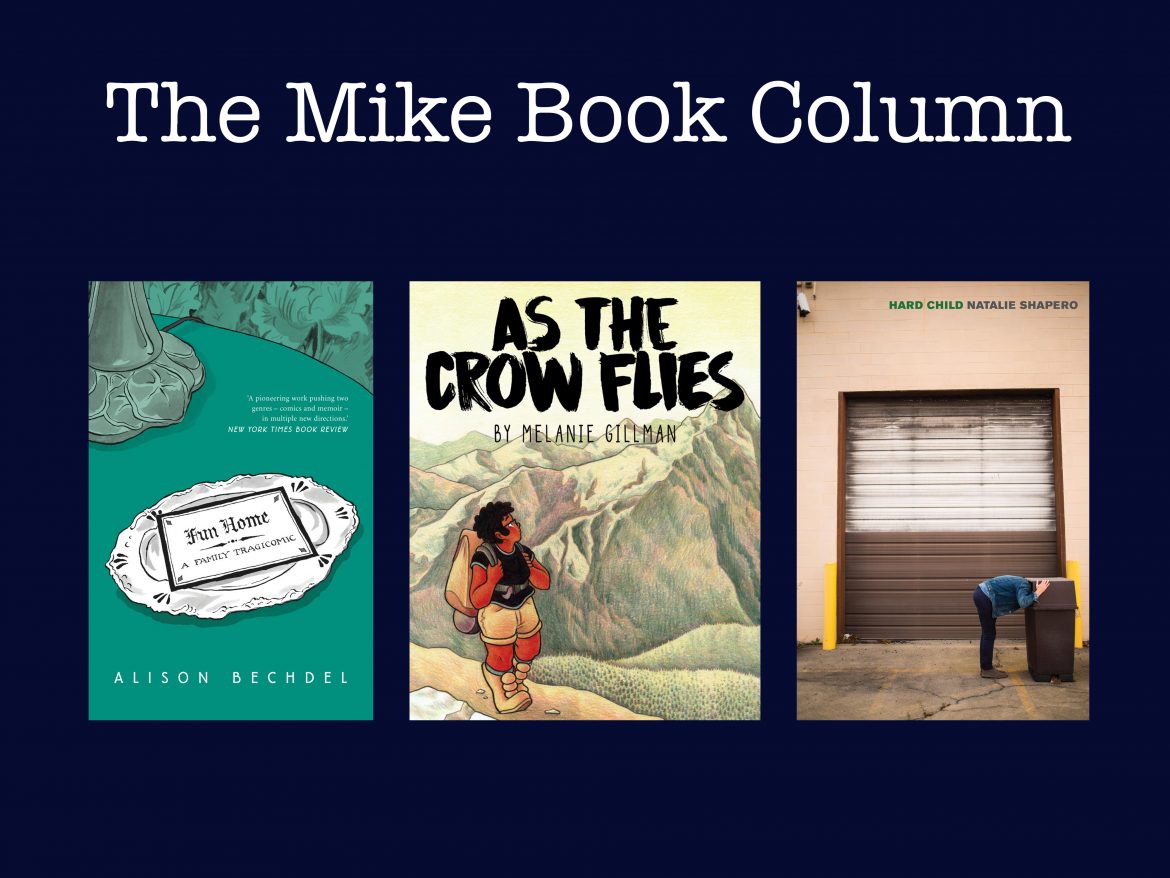

This reading week, I visited (and re-visited) three books that I had been meaning to for a while now. Distinct from one another, but with a common thread emphasizing something stark and strenuous in terms of familial and societal relations (that each book tries to unravel in its own way), I present to you: one graphic novel composed entirely of colour-pencil drawings, an autobiographical graphic novel in a blue-green hue of literary references and dysfunctionality, and a poetry anthology that infuses the lyric poetry form with crisp and unwavering intensity.

Book Review: As the Crow Flies, by Melanie Gillman

A graphic novel that needs to be nudged out of the nest

I came across Gillman’s graphic novel online some 5 years ago. Seeing a comic composed entirely of colour-pencil illustrations, addressing the intersections of the young protagonist’s experiences with being Black and Queer, left As the Crow Flies firmly stamped in my memory until I could read it today. The story was left unfinished online, but the print copy of the book gestured towards completion.

While I was finally able to access the printed copy of Gillman’s novel, I would not call this story complete. The story is set in a Christian girl’s hiking trip, a five-day journey up a mountain towards a peak that promises a “ritual of purification.” The head instructor of the venture calls it a way of “whitening our souls” at the beginning of the novel. This puts the protagonist, the fourteen-year-old Charlie, in an uncomfortable position. From the start of the comic, she is keenly aware that “All the other girls are white.” The whole concept of the camp, spurred on by the head instructor, leans on an extreme version of feminism, leaning on misandry and excluding narratives other than a white, cisgender, heterosexual viewpoint. Charlie has to deal with feelings of self-doubt, discomfort, and danger as she navigates the same mountain-path as the other girls. Gillman brings her struggles and the disparity in her experience to the forefront, as everyone else focuses on getting to the final destination of their journey.

Before they reach the top of the mountain, however, the comic ends. No closure is given to Charlie’s discomfort – nor to her exploration of her own identity in terms of her queerness and her spirituality. While the comic concludes in a moment of poignant and insightful solidarity between Charlie and another girl in the camp, a lot of the nuances that the novel gestures at never get addressed. This may be the point, as a lot of marginalized youth face experiences that are afforded no closure – but there’s much left in the story to elaborate on and to be deliberate with. While Gillman has planted the seeds for an important and nuanced narrative, they have a long way left to grow.

Book Review: Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, by Alison Bechdel

Putting the “home” in dysfunctional

Alison Bechdel’s graphic autobiography has been around since 2006. It has been in my periphery for years and has been mentioned to me by countless friends and classmates. This reading week, I decided to give it the space to breathe. I was already aware of the content warnings associated with the book: death, homophobia, parental neglect, pedophilia, and suicide, and would like to make those warnings known for any reader who wishes to continue with it. While the warnings are truly elaborated on, Bechdel does so in a complex and nuanced way that only an autobiography could convey.

The graphic novel depicts its story through a simple comic panel style with white and blue hues. Minimal, but with a lot of text, the novel leans on the narrator’s perspective as well as a slew of literary quotes and references to immerse the reader in its narrative. Bechdel writes of her childhood and young adulthood, her family, her exploration of her own identity, and her father. The novel is divided into seven chapters, not in a chronological order, but tied by the narrator’s consistency, each revealing more to the reader and deepening their understanding of Bechdel’s story.

I hesitate to call it anything but “Bechdel’s story.” To call it just “a story” would not do it justice. It is tied to the protagonist, the narrator, and thus the writer of this autobiography. It uses illustrations to draw the reader in at the right times and in the right places, while constantly emphasizing this need to look, and be, with the narrative at hand.

People were right to recommend it to me, and I intend to re-read it in future as I’m sure there are details in Bechdel’s art that I would like to pay more attention to. I would recommend it to any reader who can manage the emotional state and space to navigate the content warnings, and who wishes to see how a graphic novel can so concisely (and yet never completely – I would never want anything so exacting) capture a voice in a life, situating itself in the complexities of dysfunction, identity, and human relationships.

Book Review: Hard Child, by Natalie Shapero

Now, I wish I could have a single day of language

Natalie Shapero’s poetry is striking and unflinching. I had known this ever since I first read “An Example” in one of my English courses. I immediately needed to read more of her work so I set out to do just that during the reading week.

In Hard Child, Shapero’s lyric poems often center around the concept of motherhood and the turmoil that rises from the thought of bringing a child into this world. I would not wish to label this compilation as one thing or the other, as each poem contains a multitude of concepts and readings that can’t all be distilled to one word. Instead, I’d like to comment on how, in this compilation, Shapero spans modern-day language and widens it into the narrow corners of visceral experiences. She draws insightful, wandering observations into a bodily experience in parts of her poems, like how a little dog might “make her muscle known to every statue” in “Not Horses,” or how one “can’t go anywhere these days / without being told a turtle / has nerve endings in its shell” in “Can’t Go Anywhere.” She also often includes phrases in her poems with uppercase letters, signalling a sort of quotation or found-poetry outside of the text, yet always relevant (sometimes central) to the poem itself. Shapero uses images in an almost stream-of-consciousness way, though sparingly. She writes about the body through the body, but also through the reflective and intimate perspective of the speaker.

I wish I could write about each poem, one poem at a time – write paragraphs on each line, and each word, but that will have to be saved for a later time. In Hard Child, some poems might strike the reader immediately (“Not Horses” and “You Look How I Feel” did that for me), some might want to make one crawl up into a ball and wait it out until the world is safe (“Monster,” and “Red”), and some might take a while to unravel further (“Four Flashes”), but all poems ask the reader to face the words they set forth – to read them, and feel, and reflect on them in the same way that the speaker does.