Photo Credit: Sergei Supinsky

Despite the Russian invasion, the West shouldn’t glorify Ukrainian democracy

Tony Xun, The Mike Contributor

On February 24th, the Russian Federation launched a large-scale military invasion of Ukraine, dramatically escalating a conflict between Ukraine and Russia that had been simmering since 2014. Russian forces advanced from Belarus, Crimea, and Russia itself, bringing the conflict to major Ukrainian population centers including Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Kherson. Since then, hundreds of Russian soldiers and Ukrainian civilians have died in the conflict, although exact numbers are disputed by the belligerents. The crisis has captured global audiences, especially in North America and Europe, where most countries are members of the European Union (EU) or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The war has swiftly come to epitomize monumental shifts for the geopolitical order. Speculation about the implications for Ukraine and Russia’s respective relationships with the EU, NATO, and the world as a whole has been widespread and varied.

Media coverage in the West has prominently featured narratives that celebrate the heroism of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky and the Ukrainian cause. Western governments have loudly protested Russian aggression with the language of righteous indignation. Russian President Vladimir Putin has come to embody an insane dictator aggressively strong-arming a sovereign nation. Ukraine, on the other hand, has come to represent a bastion of human rights and liberty, proudly and defiantly led by President Zelensky, an icon of freedom. Russia’s attack on Ukraine has often been seen as an attack on the democratic world as a whole, a struggle against despotism in which all lovers of liberty must pick a side. The morality and democratic character of Putin’s behaviour is uncontroversial outside of Russia and is not the subject of this article. However, Ukraine’s reputation as the frontline for freedom and democracy is both newfound and misleading. Let’s take a closer look into Ukrainian politics and its spotty relationship with democracy and pluralism.

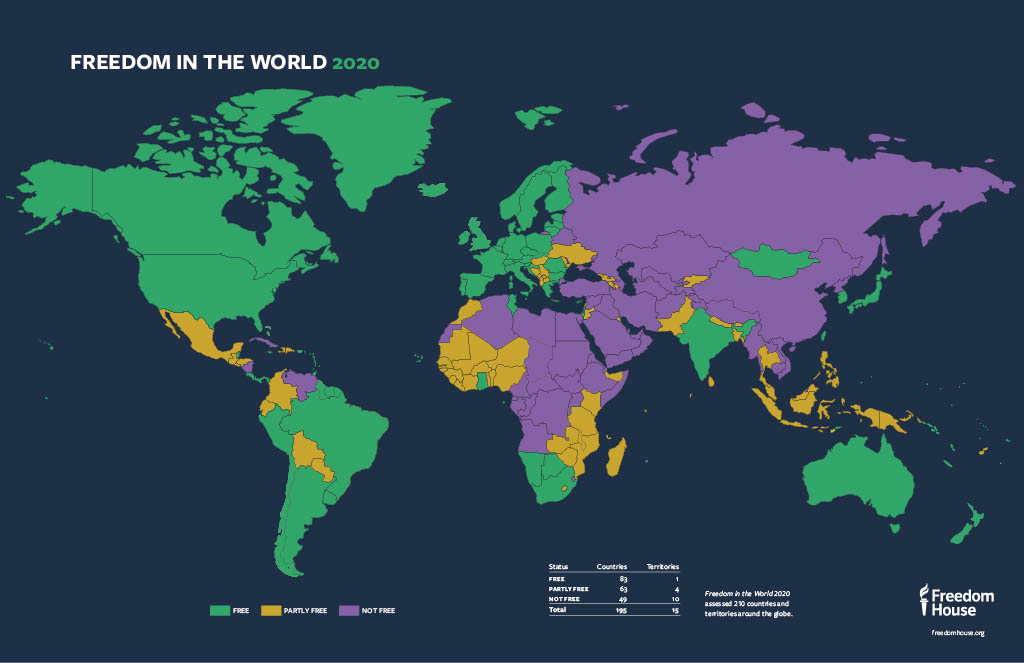

Political scientists consistently call Ukraine a “hybrid regime”. Ukraine’s political system doesn’t match the kind of liberal democracy typical of countries like Canada, Norway, and Japan, but neither is it a full autocracy, like North Korea, Russia, or Saudi Arabia. Freedom House, a nonpartisan organization that ranks democracies, gave Ukraine a freedom ranking of 61 out of a total score of 100 in 2021. Compared to Russia’s score of 19, Ukraine’s score inspires optimism, but it pales in comparison to Canada’s score of 98. The Economist scores Ukraine at 5.57 out of 10, and Freedom in the World gives Ukraine 60 out of 100.

Ukraine joins India, the Philippines, Nigeria, and Mexico in the “Partly Free” category of Global Freedom scores. (Freedom House)

Ukraine’s reputation as a free democracy has been severely undermined by electoral irregularities throughout its history as a democracy. Since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukrainian elections have habitually been decided across linguistic and ethnic lines, pitting Russian-speakers in eastern Ukraine against Ukrainian speakers in western Ukraine. Election legitimacy has been tainted by widespread voter fraud allegations – a 2010 survey found that about 20% of Ukrainians were willing to sell their vote in that year’s election, compared to less than 10% who believed that the election would be fair. Vote-buying allegations have persisted through Ukrainian elections in 2014 and 2019. Presidential candidates have long alleged that elections have been rigged against them. The Orange Revolution helped overturn the results of Ukraine’s 2004 election, and runner-up candidate Yulia Tymoshenko accused former President Viktor Yanukovich of rigging the 2010 elections.

2010 Ukrainian Electoral Map compared with map of native Russian speakers shows how deeply Ukrainian politics has been divided on ethnolinguistic lines. (Ukraine Central Election Commission)

Ukraine’s democratic institutions themselves have suffered from chronic instability. Ukraine does not have a long history of a continuous democratically elected government. Revolutions overthrew governments and forced out presidents in the 2004 and 2014 elections – President Zelensky’s election in 2019 was widely seen as the smoothest and most legitimate transition of power in Ukraine’s democratic history. Ukrainian politicians have a history of retaliating against political opponents. President Yanukovich used democratic institutions to jail Tymoshenko in 2011, and President Petro Poroshenko systematically removed members of the previous government in 2014.

Ukraine’s surface-level institutional problems already call into question political freedoms in Ukraine and the legitimacy of its governments. However, Ukraine’s biggest barriers to representative government lurk just beneath the surface in the form of corruption and the influence of oligarchs. A legacy from the Soviet era, endemic corruption is a common feature of Ukrainian society and dominates Ukrainian political discourse. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index scores Ukraine at 32/100, the second-lowest score in Europe after Russia. Former President Poroshenko and President Zelensky were both implicated in owning personal offshore companies, commonly used in money laundering, by the Pandora Papers in 2021. Ukraine’s courts are widely perceived as corrupt and primarily interested in defending their own interests and those of a corrupt oligarchy. President Zelensky has accused the judiciary of taking bribes and failing to investigate corruption cases, accusing them of blocking anti-corruption legislation. In response, the Constitutional Court questioned the legality of Zelensky’s asset declarations legislation and the High Anti-Corruption Court. The courts’ failure to prosecute oligarchs and the politically protected have meant that no cases have pursued any former member of the Yanukovich or Poroshenko administrations, despite estimates of over $40 billion of government funds lost to corruption. Corruption threatens freedom of speech in Ukraine – despite hundreds of attacks against journalists reported every year, no one has ever been prosecuted for the murder of a journalist. As a result, 78% of Ukrainians don’t trust the judiciary as a whole, including 70% who don’t trust the National Anti-Corruption Agency.

Perhaps the most odious obstacle to true Ukrainian democracy is the influence of oligarchs over Ukrainian society. Despite repeated accusations of ties to criminal elements, corruption, and stealing from government positions, oligarchs operate with impunity from the prosecution of courts. They exercise enormous control over Ukraine’s highly concentrated media landscape and weaponize their networks and TV channels to side with specific politicians. Despite anti-corruption rhetoric, Ukrainian politicians themselves are often implicitly backed by oligarchs, and are popularly perceived as representing their interests. President Zelensky has been criticized for his ties to oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, who owns the channel that produced Servant of the People, the TV show that rocketed Zelensky to fame. Members of Zelensky’s cabinet have been tied both to Kolomoisky, who supported Zelensky during the 2019 election, and Rinat Akhmetov, the 327th richest man in the world. Many oligarchs hold political positions themselves, such as former president Poroshenko, who owns Roshen, a chocolate brand. During the Covid-19 pandemic, oligarchs have expanded their personal regional influence and alleged influence over Zelensky’s government as his popularity waned.

Oligarch Control of Ukrainian media. Kolomoyskyi and Akhmetov are notably rumoured to hold influence in President Zelensky’s government. (Ukraine World)

None of these criticisms of Ukraine’s democratic institutions are to imply that Ukrainian democracy is completely hopeless or to justify Russian military activities. Ukraine’s democracy can be congratulated on its achievements and reformed where it stumbles. Ukraine may have a democratic shape, but painting Ukraine as a beacon of freedom is misleading. Supporters of Ukraine should be aware of its true status, and Western governments should hesitate to paint over the failures of President Zelensky and Ukraine’s political system in an effort to whitewash the Ukrainian cause.