Photo Credit: Ali Akberali, Photographer

Reflections on the late queen’s death

Victor Buklis, Editor-at-Large

As is now hardly news, on September 8, 2022, Queen Elizabeth II, the longest-reigning monarch in British history, passed away. With the end of a 70-year reign comes the accession of a new king, Charles III, and a time for mourning and reflection on the queen’s legacy.

On one level, everyone knew that the queen would not live forever, and so her passing was in some sense expected. She lived until the age of 96, a long life by all accounts, and we do not yet know the official cause of death.

On another level, it was unfortunate to hear that the queen had passed away. Why this would be my own response to the announcement of the queen’s passing, however, puzzles me.

There are two relevant facts about me that make me ask why I would have any fondness for the late queen. The first is that I am a Canadian who has always wanted to be an American citizen, and who has always described himself as being an American at heart. The second is that I am a Roman Catholic. So I wonder: apart from its consistent presence on the news, why would I be much affected by the topic of the queen’s passing? Why does the topic even interest me?

It would be fitting, of course, to say more about the two facts just mentioned. Let’s begin with the first fact, that I am a Canadian but otherwise call myself an American at heart. What this means is that I am a Canadian citizen — born here, raised here, lived here my entire life — who has an undying love for the United States. Ever since I was young, I have compared the US favourably to Canada and have wanted to move there. Many years back, I even took pains to study various American accents and how they compared to Canadian accents. The goal of such an activity was to ensure that, whatever I sounded like when I spoke, it wasn’t Canadian. I thus did my best to eliminate Canadianisms from my vocabulary (I used few of them anyway) and altered my pronunciations of certain words and vowel sounds so that people would hear an American accent when they heard me speak. Likewise, when not constrained by a style guide insisting otherwise, I prefer to use American spelling conventions to British and Canadian alternatives. A description of my efforts along these lines could fill many pages, but that is another story.

A consequence of my admiration for the US is that I am attached to its political system as well. The Constitution, which expressly limits what the government can do; the separation of powers among the three federal government branches of executive, legislative, and judicial; and the electoral college all fascinate me, along with other aspects of US governmental structure. Also, the US is a republic. This means, of course, that it is not a monarchy of any sort (constitutional or otherwise). And the late queen was, by definition, a monarch. Hence my wonder: if I have such admiration for the US and its republican government, why have any interest in the passing of the leader of a monarchy? It doesn’t help that the monarchy at hand was the very government that the Thirteen Colonies declared independence from in 1776 to become the US.

Let’s move on to the second fact, that I am Catholic. What is surprising here is not so much that it is hard to imagine Catholics expressing general approval of Queen Elizabeth II — it’s not. But the fact is that the queen was the head of a church, and that church was not the Catholic Church. The queen was the head of the Church of England. In fact, she was the supreme governor of that church.

The title “Supreme Governor of the Church of England” has origins in a famous episode of English history in which the king at the time created his own church simply so that he could leave his wife. In the late 1520s, King Henry VIII was married to Catherine of Aragon, but he was concerned that she had not borne him a son, meaning he would have no male heir to the throne. He wanted an annulment, but Pope Clement VII would not allow it. Eventually, in 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, which gave to the English king the title of Supreme Head of the Church of England and formalized a split with the Catholic Church. The king now took the pope’s place as leading the church in England. Later, in 1558, the monarch’s title changed to “Supreme Governor.” But, in any case, the pope would no longer have jurisdiction over the English church.

To connect this to the present circumstances: Queen Elizabeth II, as the English monarch, was the head of a church (and a member of the same) that started in explicit rebellion of the pope’s authority over the universal Church. And as a Catholic, I recognize the pope as the Church’s leader, not the queen. So again: why feel the need to mourn the queen’s death?

Furthermore, taken together, why would a Catholic American-at-heart have any interest in mourning the queen’s death or be sad to see her go? That’s two counts against the question of whether to mourn or not.

One clue that might lead to an answer: what’s next for the English crown? Will things stay the same, or are serious changes on the menu? Certain changes, at least, are likely. For instance, King Charles III is 73 years old, and he has reigned for less than a month. By the time his mother was 73 years old, she had reigned for 47 years already. At that point, it was 1999, and Queen Elizabeth still had more than 23 years left of her reign. In other words, if the new king lives to the age of his mother, he will sit on the throne for more than 22 years as his birthday is in November. If he lives to 100, he will reign for more than 26 years. That would be a long reign by most standards — as holding an institutional leadership position for a quarter century is no small feat — and hopefully he accomplishes it. But, realistically speaking, the new king will not reign for as long as his mother did. The question of royal succession in Britain will thus stay in the public mind for much longer than it has over the past 70 years.

Another potential change is whether the king will be politically involved or not. King Charles has already noted that he will not continue his past activism, such as on environmental issues, as king. In his inaugural address, Charles said, “It will no longer be possible for me to give so much of my time and energies to the charities and issues for which I care so deeply.” By the sounds of it, he wants to follow in his mother’s footsteps and be a stabilizing presence in British society. So far so good.

But the new king has chosen to be called Charles, and the story of one previous English king with that name bears repeating. In particular, King Charles I reigned from 1625 until 1649. He professed a belief in the divine right of kings — the idea, used by absolutist monarchs, that a ruler’s authority comes from God such that the monarch is immune from popular accountability — and was determined to govern England as such. For example, he dissolved Parliament in 1629 and tried to rule without it for 11 years, only convening it when he realized that he needed Parliament’s help to raise money for a war he had gotten himself into. Also, the English Civil War broke out during his reign and pitted supporters of the king against supporters of Parliament. Finally, as is permanently etched in my mind by the 1980s Monty Python song “Oliver Cromwell,” Charles was tried and convicted of treason for his tyrannical reign and then, in 1649, was beheaded.

When Charles III picked his name as king, he might have simply been choosing to keep his given name, as Elizabeth II did. Fair enough. But he ought also to know the connection between his choice and the not-so-fondly remembered king of the mid-17th century. Moreover, hopefully he makes good on his word and does not emulate said king’s drive to rule without regard for Parliament, given Charles III’s heretofore propensity to speak his mind about the issues of the day.

A third question is whether King Charles will be as popular as his mother. As of the second quarter of 2022, YouGov polling named Queen Elizabeth II as the most popular British royal. She had, at that point, a 75% popularity rating. A politician with comparably high approval ratings would be someone like John F. Kennedy, US president from 1961–63. By contrast, Charles is the seventh-most popular royal, and he had a 42% popularity rating. That number is comparable to the approval ratings of the two most recent US presidents: Donald Trump and Joe Biden, neither of whom are popular. Can the new king achieve a high level of popularity and be a unifying figure, like his predecessor? Only time will tell.

All things considered about Charles III, perhaps it is easier to answer the original question about my interest in Queen Elizabeth’s passing. On one hand, about the religious aspect: my main interest is about the queen not insofar as she was a religious figure, but insofar as she was a symbol of national unity and stability. Members of the Church of England may have looked to her as their official leader, but others could simply admire her stability and popularity.

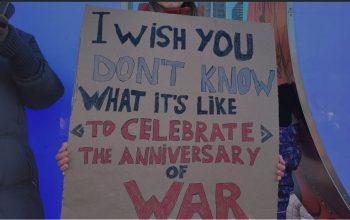

And about the US versus UK aspect: I might love the US, but an unfortunate feature of American society today is that little seems to unify people across the country. The US, as a republic, does not have a monarch, but in its absence, what institution do (or should) people rally around? I think there are a handful of candidates, like the presidency, the courts, the electoral college, the Constitution. However, at the current moment, even these institutions are not universally cherished. They may have been more popular at different times in US history, but still, for instance, it’s not as if every president of the last 70 years has been as popular as the late queen. Maybe it is just nice to have seen in Queen Elizabeth II a rare figure behind whom citizens (of more than Britain) could stand proudly.

All this goes to show that some national figures find themselves able to gain the approval, respect, and admiration of even the most unlikely people. In this case, the national figure was Queen Elizabeth II, and the unlikely person was me, a Roman Catholic Canadian who has always thought himself more American at heart than Canadian.