Photo Credit: Wikipedia

The ancient origins of Halloween

Zenon MacKinnon, Logos Editor

Spooky season is around the corner. You might have already picked out a costume for parties or gone to haunted houses. For those of us who are Catholic, Halloween is also the eve of All Hallows, a day commemorating all the saints, whether known or unknown. The following day, November 2nd, is All Souls’ Day, commemorating all Christians who have passed away. Together these three days are known as Allhallowtide. And whatever spooky celebrations or commemorative rituals you take part in this time of year, they have deep ancient roots.

The practice of dressing up in costume on Halloween, for example, has its earliest attested antecedent in ancient Roman funerals. When a great man died, his family would bring out the funeral masks of all their greatest ancestors and dress up as them. They would march in procession toward the wake, displaying symbolically the ancestral spirits whom the deceased would now join.

The timing of Allhallowtide also has pre-Christian origins. The Celtic pagan holiday of Samhain coincides with Allhallowtide and likely played a role in determining its dates. At Samhain, the Celts marked the end of harvest season and the beginning of the darker half of the year. They believed that their seasonal festivals were times of the year when fairies and spirits could more easily pass between their world and ours. Jack-o’-lanterns come from this pagan festival and were originally meant to scare away any evil spirits.

Our Halloween tradition of trick-or-treating also comes from the mists of time. In medieval Western Europe, children and beggars would go door to door asking for “soul cakes,” a kind of round dense shortbread often flavoured with spices. This itself recalls an early tradition, related to Christmas carolling, called “Wassailing.” Coming from the lifeways of pagan Germanic warbands, this was originally a practice where groups of rowdy young men would, at certain times of the year, get together to sing and to demand free food and drink from wealthier but weaker targets. Gradually, wassailing was domesticated and became a tamer, more generous, and more friendly practice done in orchards and among friends.

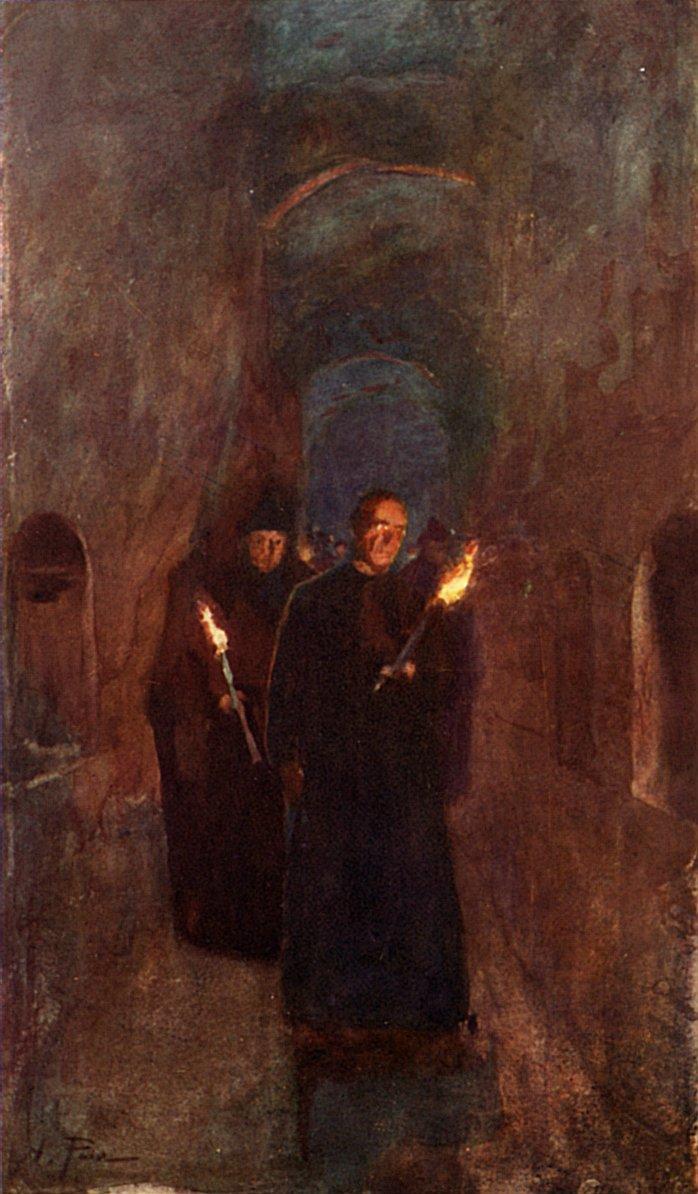

None of this is to say that Allhallowtide today is somehow pagan. The impulse to commemorate the dead with rituals and time set aside in the cycle of the year is perennial, but it would be intellectually dishonest and lazy not to treat each instance of it on its own terms. Allhallowtide has its theological origins in the Christian doctrine of the three states of the church. The first night, the Church is in her “militant” state — that is, fighting against sin on earth — and holds a vigil the eve of All Hallows. The next day, the Church remembers all her members who are “triumphant,” which is those who have entered into full union with God, beholding Him in Heaven. Finally, on All Souls’ Day, the Church remembers her members “penitent.” This constitutes all the dead who are not saints, who wait to be washed of their sins in Purgatory.

All these ancient and medieval traditions we live out on Allhallowtide serve to remind us that we live in the world our ancestors built. Even things as seemingly innocuous as dressing up in a costume connect us to the lifeways and worldviews of those who came before us, whether we think about it or not. For my part, as much as I like dressing up and going to parties, the most touching of these days is All Souls’. I go to church and light candles in graveyards — I pray for everyone I knew and loved who has now passed on. But it’s also a time of reflection for me for all the many generations of cultural evolution, exchange, and practice that brought our society into being. Millennia of little traditions cumulatively make a civilization that has been constructed by men and women long dead whose names we will never know.