A docudrama that aims to add humanity to history, through frames of film

M.A. Kalaczynski – COPY EDITOR

It is obvious from the start that Poland’s history in general has been one of conflict and turmoil, whether it be in a distant past such as Grunwald in 1410ora more recent one, such as the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. It is therefore no surprise that many of Poland’s directors have chosen to focus their skills and cater towards these memorable historical events.

Janusz Zaorski is no different in this respect. He includes in his docudrama snippets of various films by well-known and respected Polish directors and Zanussi, and others.

However, one very important thing that Zaorski does through his film Generations is go beyond just the cinematization of a conflict for the 21st century audience of a Hollywood-style production, instead aiming to present a weaving narrative through the connections he sees, linking all the films he chose.

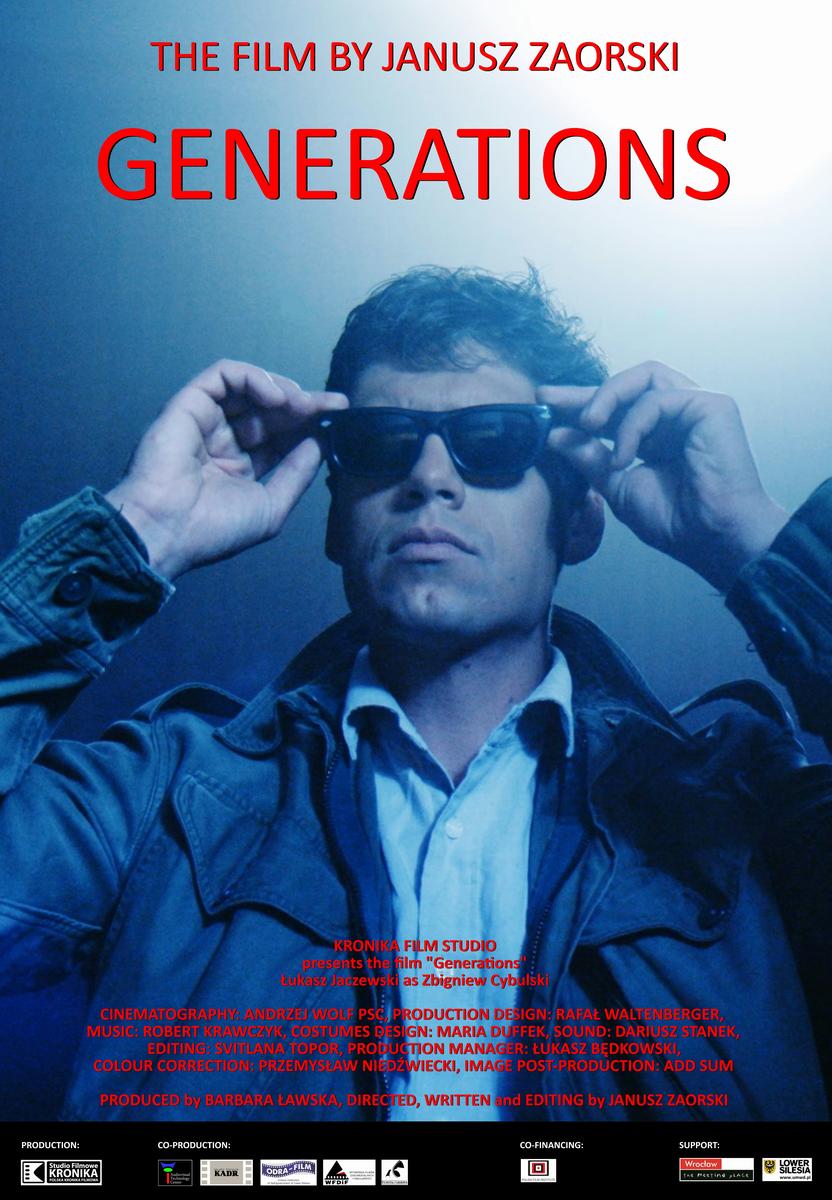

One of these aspects is the portrayal of Zbigniew Cybulski. Not only is he featured in many of the films chosen for Generations, but he also exhibits an “out of film” presence as the audience’s “guide,” throughout. In the opening scene of the first feature presented, he is drinking a magical potion that results in him being sent through time and space in the following films. In truth, Cybulski is directly involved thereafter, either as a character or through the snippets presented as an audience member in the Wrocław Film Studio.

Another one of these connections is the nostalgia or longing for what Zaorski described as a “beautiful, sentimental note of time past.” While it is evident that these films all possess an air of the periods they were produced in, they are not always presented in those times at their release. For example, many films about current events were not allowed to be produced under the Communist Regime after WorldWar II, and therefore, there was a surge in film production regarding the past in the 1980s and 1990s.

AnotheroftheseconnectionswasbroughtupbyUofTProfessorTamaraTrojanowskaatthe post-film discussion. She saw Generations as a “cultural history of love,” in the way that the film dealt with and presented snippets of male/female relationships. This is evident through the various scenes of love, embrace, and carnal relationships presented all along different film scenes. Zaorski’s response to this was that he felt the need to include this aspect of human life into his feature, as he saw the politics the film dealt with as dull and “like a newspaper;” not representative of the young generations of both audience members and directors. Of course, this is obvious, as the film has to deal with the various complicated aspects of post-war history — as Zaorski describes “the Nazi occupation, Stalin terror, Gomułka, and Jaruzelski and Solidarność.”

Not only do the times the films were produced in reveal aspects of that time period, but the films should be considered as responses to current events. It is impossible to remain indifferent to the context in which a film is produced, as societal elements included in this film unintentionally show through: for example, furniture, cars, clothing, references to popular culture, etc.. An audience member does not need to have extensive background knowledge of when all a chosen films was produced, as elements of the films make it known. For example, it is obvious when a film is produced in the 1950s versus the 1970s both in terms of set and props but also in the thematic concepts the film deals with, both directly or indirectly.

The most interesting aspect of this docudrama lies in the variety of films and film scene types presented. Zaorski didn’t choose one type or set of scene from any specific time. Instead, he made Generations focus on all aspects of the human experience. Specific examples of famous scenes of Polish filmography were present, as were legendary cult classic identifiable by anyone, such as Andrzej Wajda’s Popiół idiament (Ashes and Diamonds) scene at the bar with the lighting of the vodka to remember those fallen in the Warsaw Uprising, or Sami Swoi, another cult Soviet-era classic. Even then, the scenes were never so long as to incite boredom, but just long enough to interest the audience as to how the particular scene fit into the docudrama.

Even though one may not have seen or even heard of every single film featured in Generations, itwasimpossibletogetlostasthescenesZaorskichosedidnotcallforadeeperanalysisor understanding of the entire feature film, but only of the precise moment of humanity that shone through and linked all the scenes together — snippets of films as s reflection of the history of Poland as told on screen.