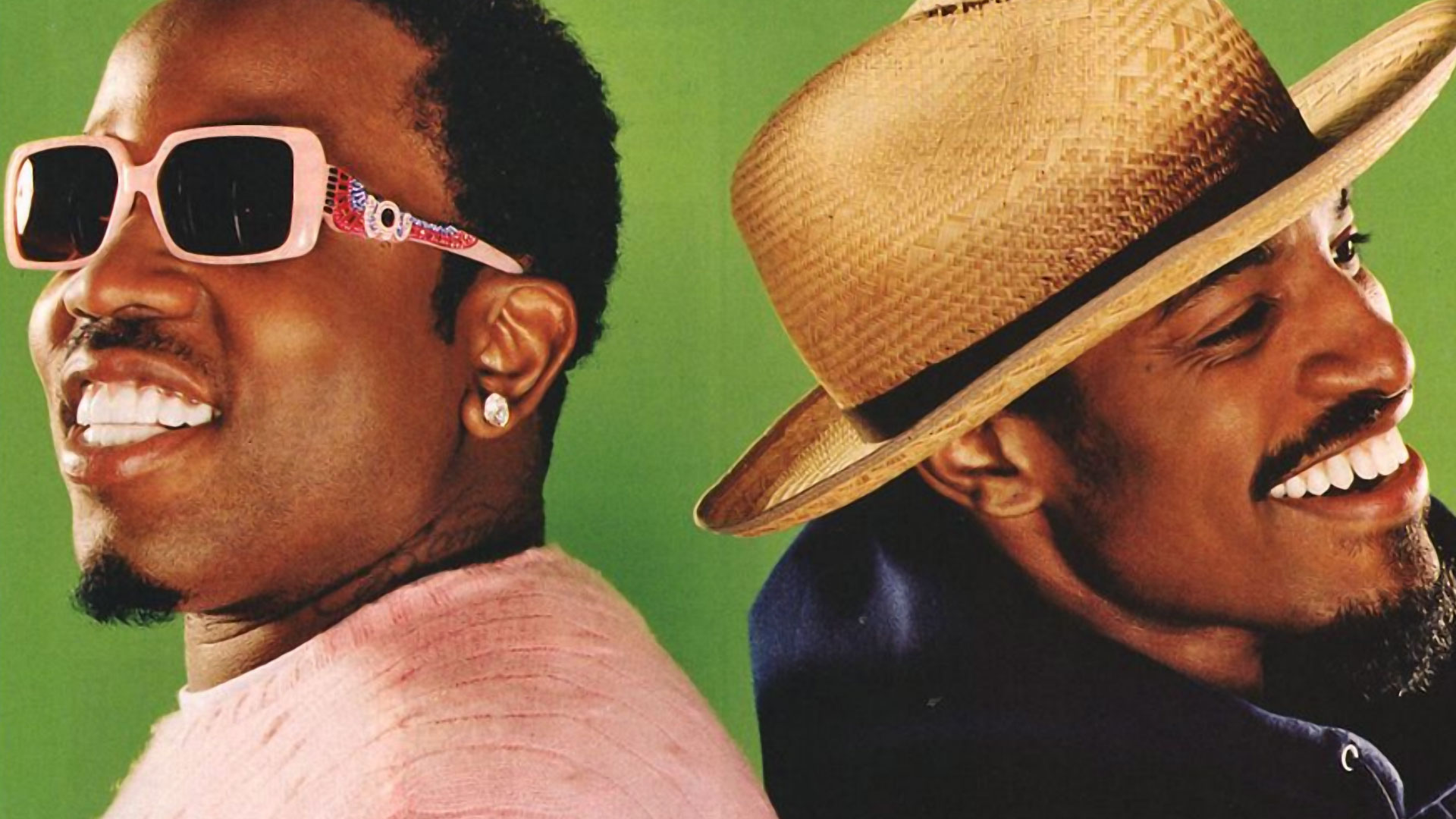

A Retrospective / The Case for OutKast’s Greatness

Rory McCreight – SPORTS EDITOR

Now, I am well aware that calling a band — especially one from the last couple of decades — “the best band in America,” is a heinous act. It is arrogant, subjective, and unnecessary; nevertheless, to the doubters I say, “listen to OutKast, The Greatest American Band, and step back.”

Perhaps some individual acts could be argued for against OutKast: maybe The Boss, Prince, Bob Dylan or the jazz legends. Still, I think that at their best, these legends owe a serious (and underacknowledged) debt to their bands: in the case of Bruce’s E Street Band, Prince’s Revolutions, and Dylan’s The Band. OutKast on the other hand, was always two; even when they were separate ones in a single package, they were intrinsically linked. Whatever your stance, have a look back with me at an undeniably singular band, from a singular time and place, that created some of the most unique and exciting music of the last 30 years.

In 1991, Andre “Andre 3000” Benjamin and Antwan “Big Boi” Patton met at a local shopping mall near where they lived in Atlanta, Georgia: where they also attended high school together. Big Boi had moved from Savannah to Atlanta with his ten siblings (four brothers and six sisters), and Andre was living with his father following his parent’s divorce. The two fast became friends and soon began battle rapping in the school cafeteria together. Their first album (Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik) as OutKast was released in 1994 when the duo was still in their teens and was a commercial success: it went platinum with its lead single, “Player’s Ball.”

Now, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik does not have the idiosyncrasies that would come define the bulk of OutKast’s output. Rather, it is a pretty straightforward southern rap album with two talented and young MCs bolstered by live instrumentation and the novelty of southern rap in an era dominated by dueling East and West Coast rappers.

OutKast’s outsider status to an ancient rap feud gave them their first big moment in the spotlight. At the 1995 Source Awards, OutKast took home best new artist honours amid a tense Madison Square Garden. In the face of a conflict that would turn terminal when both Biggie and Tupac would lose their lives to the violence, two oddballs from Atlanta, wearing their hair big and au natural, and Andre in some Prince-like purple, told everyone: “The South got something to say!”

OutKast’s second album, ATLiens, not only helped establish the group as a force to be reckoned with, but came to define the southern rap sound as a whole. Andre, who committed to a clean and sober lifestyle prior to work on the record, was its guiding force. His odd presence defined the alien identity that the band performed through on the record. Big Boi was no slouch, but the blueprint for the record screams Andre — alien voices creep in the background, airy synths play alongside record scratches as the MCs hover over their beats like extraterrestrials taking in a foreign land. Andre raises himself above the destructive rap beefs du jour — in “Two Dope Boyz (In a Cadillac),” an anonymous rapper challenges Andre to a rap battle and Andre just dismisses him: “This ol’ sucka MC stepped up to me / Challenged Andre to a battle and I stood there patiently / As he spit and stumbled over clichés, so-called freestyling / Whole purpose just to make me feel low, I guess you wilding / I say look boi, I ain’t for that f*ck shit; so f*ck this.” Among other things, this showcases how Andre and OutKast were throughout their career. They never seemed on the same level as their competition, rap or otherwise: their output was singular, otherworldly, and inimitable.

By their third album, Aquemini, OutKast had perfected the sound and identity from ATLiens — they were southern alien rappers. Each of those three designations revels in contradiction. Their southernness gave them deep sonic and personal roots to the delta blues, P-Funk, soul music that is entrenched in both their sound and personal histories. But they were also foreign, unattached beings that floated above it all, as they tried to free themselves from the cosmic forces that determined their birth. On top of it all, they were also accomplished rappers, two under one identity. While rappers are, historically, hyper-masculine figures with dominant, uncompromising personalities, Andre and Big Boi did their best to dissolve into a shared existence on their records.

This coexistence is part of what makes OutKast possibly the greatest American band. The two MCs acted in tandem, hence the album title Aquemini, an amalgamation of their two star signs (Big Boi an Aquarius and Andre a Gemini). A particularly excellent example of their commingled sonic identity is “Rosa Parks,” the third track on the album of the same name. The beat of the song is created from DJ scratches and drum tracks that ride with a twangy country guitar playing a boot stomping hook. The chorus of the song, “Ah ha, hush that fuss / Everybody move to the back of the bus / Do you want to bump and slump with us / We the type of people make the club get crunk,” is sung in harmony by both MCs. Its lyrics brush off Civil Rights heroes as OutKast kick back and revel not in what they do not have, but what they do — their blackness and their southern-ness.

OutKast’s fourth album, Stankonia, stands out as the strangest distillation of their artistic goal. The recurring image of an alien realm resonates with their early albums. But here, it is an alien from the centre of the Earth, from the centre of America. This is a black album, OutKast is a black band, and their music comes from the heart of their unique and quintessentially American experience. This sound is from a place buried, hidden, and forgotten, by the people who live on the Earth’s surface, and it is performed (and articulated) on the final song of the album, “Stankonia (Stanklove).”

The title track may be the great outlier of Outkast’s discography, a glimpse of what might have been had their follow-up album not been fully divided. The song sounds utterly foreign: its slobbering bass line is muted as if coming from some distant, undiscoverable party, and a ghostly choir emerges sporadically — straight out of Hades. It is the summation of the album’s sonic push: a strange and alien music from the heart of this world. The muted bass told white people that this was a sound and a party that was not for them, and reminded black people of the party that has been denied to them in America, in a fashion reminiscent of the revelry of “Rosa Parks.”

Where ATLiens and Aquemini blended Big Boi and Andre’s distinct styles into a cohesive sound with each rapping from their own unique perspectives, Stankonia presaged the division that would become OutKast’s final album, Speakerboxx/The Love Below — an album that would eventually go Diamond and cement OutKast as a pop force. The two MCs began pursuing their own unique sonic perspective. While certain songs on Stankonia sounded uniquely Big Boi or uniquely Andre 3000, this was not necessarily a bad thing. Rather, it marked their continuing individual artistic growth.

Take the nearly upsetting banger, “Snappin’ and Trappin’,” which was a quintessential Big Boi track. Big Boi’s sound tends towards the bombastic. His strategy is obvious but difficult — his tracks start out loud and get louder. The trouble with this method is twofold: justifying that initial jarring shot, and maintaining the energy throughout. “Snappin’ and Trappin’” has Big Boi in his wheelhouse, spewing braggadocio about Cadillacs, money and girls, with his laid-back cool. The song is loud, stays loud, and ends louder — it is a straight shot of adrenaline that lasts nearly five minutes in the bloodstream. (As an aside, it even introduced Big Boi’s protégé, Killer Mike, to the world. Killer Mike is best known as one half of the politically-charged and uncompromising Run The Jewels, whose third album came out this Christmas.)

Andre’s late OutKast sound contrasts with Big Boi’s bombast: think of songs like the legendary “Hey Ya,” or for example, “Humble Mumble,” featuring Neo-Soul pioneer and mother of Andre’s child, Erykah Badu. A classic Andre song starts as a typical pop song with a little OutKast flavour, whether this be something southern, or a bit of early Atlanta trap music, or some characteristic OutKast idiosyncrasies. For “Humble Mumble,” that uniqueness comes about in Andre and Badu’s natural chemistry and harmony.Despite breaking up, they never lost that je ne sais quoi on the beat. But the moment it becomes uniquely an Andre song is as it begins to fall apart. Once Andre has successfully established a melody and rhythm to a song, it starts to unravel and the song becomes a barely self-contained and chaotic jumble. The typical rap verse becomes nonexistent, the melody is lost under a cacophony of maddening brass, and Andre and guests repeat some lingering thought or just plain nonsense.

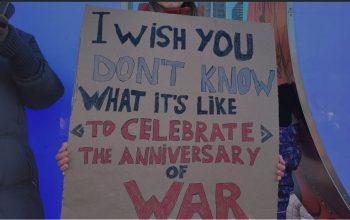

OutKast’s unmatched “B.O.B” however, is the ultimate coming together of Big Boi and Andre’s aesthetics. It is not the synthesis of their early work, it is instead more of a confrontation between their divergent and diverging identities: the bombast of Big Boi meets the chaotic unravelling of an Andre pop track. “B.O.B” starts with a breathy countdown by Andre before barreling into his mile-a-minute verse, running through everything from prison life, the anxieties of stasis, all the way to being lied to about the weather. The frantic stream of Andre’s flow and the unrelenting blast of the music create the claustrophobic feeling of living in a cramped, hot Atlanta slum, and the feeling of the un-predictableness of paradoxical inevitabilities. After the two artists deliver their verses, the song devolves into a chaos that has Andre 3000’s handprints all over it. The song alternates between call-and-response chants, a children’s choir that repeats the refrain, “Bombs over Baghdad,” and general pandemonium. The song is hectic, evocative and violent, but its sound is straight OutKast. It is danceable, it is cathartic: it is utterly brilliant. The way it parallels the slums of Baghdad under Saddam, with inner city black life, linked by nothing less than a refrain sung by children, makes for a simply manic creation.

The trail of misogyny throughout rap is often a mark against the genre; however, OutKast gave women more agency and a stronger identity in their songs (though I’ll admit, they did still occasionally dabble in rap’s misogynistic stream). The song, “Toilet Tisha” though, is a fascinating representation of a woman from a male perspective, and it conveys as understanding without being limiting. It is about the struggles of young, poor, black women facing the harsh realities of growing up too fast in an Atlanta ghetto. The song avoids moralizing — it merely attempts to represent the individual horrors of young life as a poor women, as someone whose life is rushed by impending adult responsibilities. Big Boi offers an account of the likely fear, loneliness and inability to comprehend life involved when a 14-year-old girl gets pregnant. Andre seems to be continuing a story he began in “Da Art of Storytellin’ (Part 1)” from Aquemini, in which a woman whom he grew up with was never able to escape poverty. Andre’s guilt at escaping, while others failed to, pales in comparison to the tragedy of innocence corrupted and destroyed by poverty: “In the middle of the ghetto on the curb, but in spite / All of the bullshit we on our back staring at the stars above / Talking bout what we gonna be when we grow up / I said what you wanna be, she said, ‘Alive’.”

Post-OutKast, both MCs have maintained a steady and impressive output in their own right. Big Boi, the often underrated of the two, released his first solo album, Sir Lucious Left Foot… The Son of Chico Dusty, which showcased him at his purest by jumping between wall-rattling stripper anthems while steamrolling through any rap beef to step in his path. The album delivers — it is loud, playful, and energized.

Andre’s output has been more atypical. Since his Prince indebted turn on The Love Below, Andre hasn’t released an album, but has steadily released loosey singles and shown up on big name albums to deliver some memorable verses. Verses like on the new Tribe album, with Frank Ocean and a Future feature a couple of years back are strong, but his stand out has been his track on Frank Ocean’s Blonde, “Solo (Reprise),” a track that is all his, where he details what must be a life’s worth of anxieties in just over a minute.

Andre’s solo output is marked by a subtle but clear shift in his style — he wants to clearly hear his voice. In one of OutKast’s last releases together, they were featured on the UGK song “Int’l Players Anthem (I Choose You).” As the story goes, when the late Pimp C received the track back from OutKast, he was livid that Dre dropped his drums for his verse — to the point that he nearly refused to release it. Pimp C was persuaded by an A&R rep named Jeff Sledge, who explained thus: “André had a thing. Even if you listen to André’s stuff now, he has a thing. He doesn’t really like drums under his stuff much because he wants to hear what he’s saying.” This seems to go back to the ATLiens Andre: “God works in mysterious ways so when he starts / The job of speaking through us we be so sincere with this here / No drugs or alcohol so I can get the signal clear as day.” He wants to channel and perform what he hears without any disruptions.

Whenever bands break up, it is always from the inside out — it tends to be an implosion that leaves the final albums before their official disbanding, hollow and worn out. Like everything OutKast did, their break-up was a contradiction — it was an implosive explosion that manifested in 60 tracks of uncontained chaos that made up their last two albums (“Idlewild” — their film tie-in, record excluded). “The Pimp & The Poet” could not coexist on the same beat forever, and so they eventually drifted away from each other by the karmic winds of time: one physical and the other metaphysical, one in the street and the other in his head: one that belonged to Big Boi and the other to Andre 3000. At their peak, they were the best group in America: where one lacked the other thrived, and their contradictions created a whole and made each other better. America may be the place of the singular, indomitable will, but the best band and the best music came from an intimate joining of two.