The Freddie Mercury biopic favours histrionics over historical accuracy

Nick Poulimenakos STAFF CONTRIBUTOR

Image: BUSINESS INSIDER

There really isn’t a band quite like Queen. From the way they crafted a song to the way they commanded the stage, the English band was truly one of a kind. At the centre of the band was the legendary Freddie Mercury. Known for his unique, flamboyant style, Mercury has consistently been hailed as one of history’s greatest frontmen. The entire saga of a rock band like Queen is both exciting and complex, so when the decision came to craft a film about the band, nobody was expecting the project to be pages ripped out of a history of rock textbook.

Following production troubles, Bryan Singer’s biopic Bohemian Rhapsody finally made it to theatres this month. Upon release, reviews were mixed as many criticized the film for its blatant disregard for facts. In this piece, I put Bohemian Rhapsody under the microscope to see just how much was changed for the purposes of a film narrative. The focus will be on the film’s three biggest moments: Freddie’s solo project, his HIV diagnosis, and Live Aid.

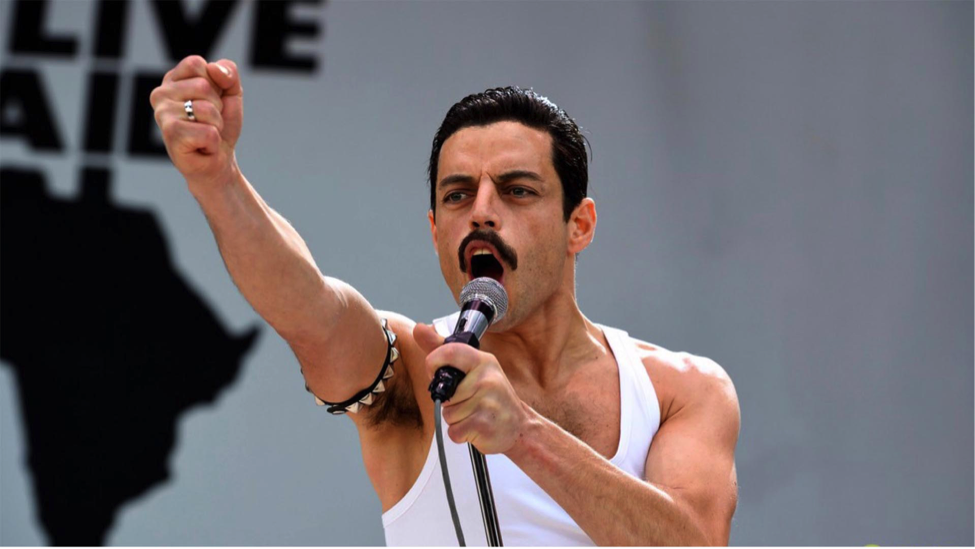

After conducting research on Queen’s history, it is apparent that the film, while enjoyable and fun, is almost entirely filled with creative liberties. Aside from a truly incredible performance from Rami Malek and a superbly constructed Live Aid concert sequence, Bohemian Rhapsody plays reckless and loose with facts in such a way that it seems like the remaining members of Queen (sans bassist John Deacon) were treated with some animosty. In short, the screenplay does nothing but rewrite aspects of Queen’s history.

Once Queen forms, Freddie Mercury, Brian May, Roger Taylor, and newly introduced bassist John Deacon begin releasing a slew of albums, earning positive reviews on each one. Freddie’s life begins growing increasingly more complex as he deals with the conflicted nature of his sexuality (which, along with his racial identity, is superficially glossed over in the film) as well as his role as lead singer of Queen. He enters into relationships with Mary Austin and later on, Jim Hutton, and continues to write music, but in the lead-up to Queen’s performance at Live Aid, something unexpected happens. Mercury decides he wants to publish a solo effort. It’s here where the film veers far off the course of history. After years of touring, Freddie reveals that he’s signed a solo deal behind the other members’ backs for $4 million and that he wants to put Queen on hiatus. The other band members are livid, and they all go their separate ways. In this moment, Freddie Mercury becomes the villain of his band’s own story.

This, however, is far from the truth. By 1983, Queen was burnt out. Touring for a decade took a toll on the band, and so it was collectively decided that a break was necessary. There is no record anywhere of the band breaking up. When Mercury’s solo career “stalls,” the movie shows him crawling back to the band with his tail between his legs, begging for them to reunite and play the Live Aid concert. Once again, not only is none of this historically accurate, but the film maddeningly omits that both drummer Roger Taylor and guitarist Brian May released solo albums before Mercury ever did.

This leads us to Live Aid, a concert that many have called one of the greatest in history. The film pulls out all the stops to get this right and delivers on all accounts. The songs, the performances, and the visual effects are all fantastic. However, almost everything that led to the concert was a dramatization designed to tarnish the memory of Freddie Mercury. The group was on speaking terms and was even recording music during the time that Freddie was working on his solo effort. They were all at peace with each other by the time Live Aid came around.

But, as the film will lead you to believe, the group initially struggled to “get back into playing shape.” Again, taking creative liberties, during Live Aid rehearsals Freddie reveals that he was recently diagnosed with HIV. The band members are shocked, but it causes them to re-focus and perfect the songs. It makes the entire concert seem like a heartfelt reunion, even though it was entirely fabricated for the film. Not only was Live Aid not a Queen reunion, but the exact time that Mercury learned he had the disease remains somewhat under dispute. Most pin it as occurring sometime between 1986 and 1987, so he almost certainly had no clue about the diagnosis when the group was rehearsing for Live Aid. It certainly makes the performance more theatrical, but the premise is false.

For whatever reason, Bohemian Rhapsody clearly went for dramatic impact over historical accuracy, making the film seem more like a commercial for Queen records than an honest portrayal of one of rock ‘n’ roll’s greatest bands. Maybe one day a studio will work to give Freddie Mercury the biopic he deserves. For now, we’ll have to settle for this: a fictitious, superficial tale of the life and times of Queen and Freddie Mercury.