Why governments need to explore funding menstrual products

Tasnim Choudhury STAFF COLUMNIST

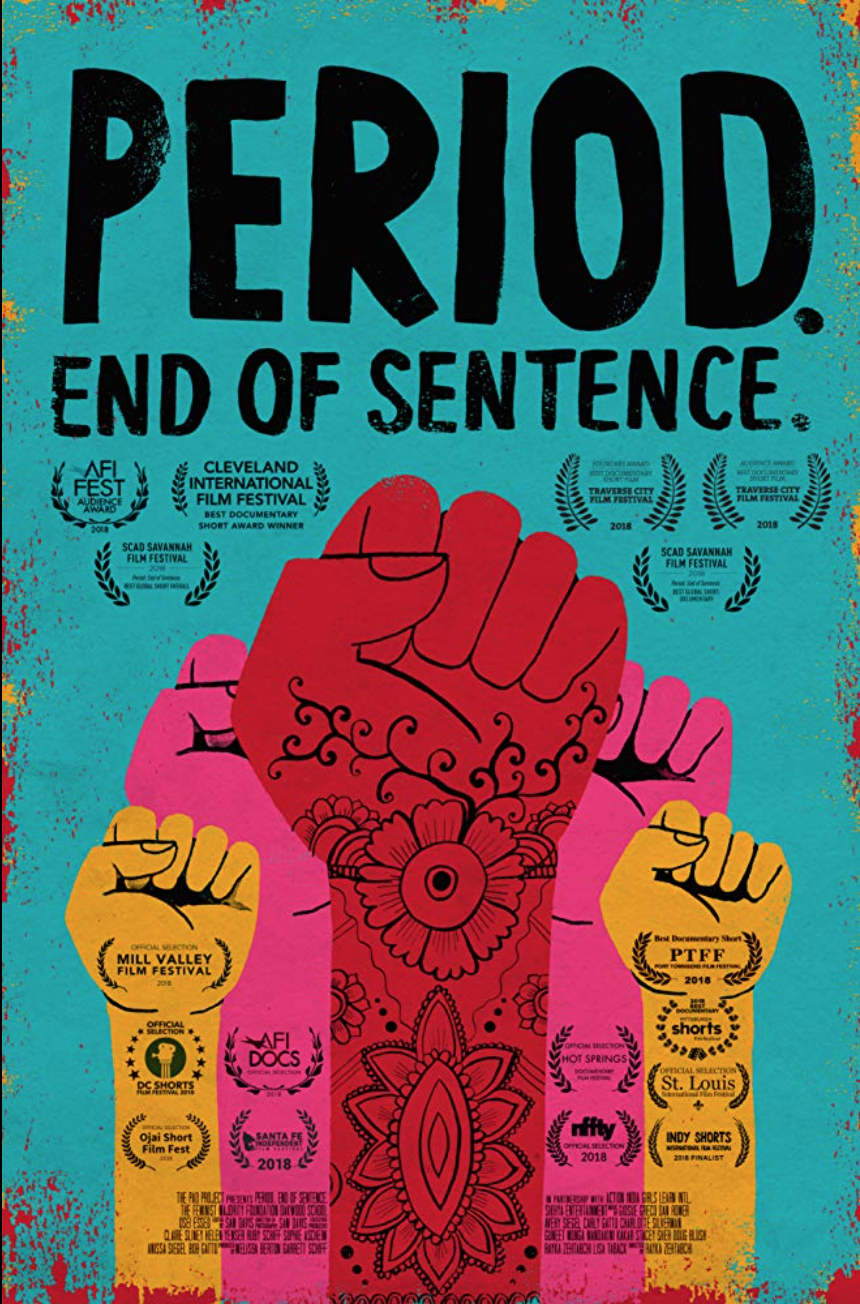

Image: NONFICTIONFILM.COM

Menstruation. A veiled term used all around the world despite millions of females experiencing it every month. The stigma and taboo around menstruation is still stuck on euphemisms such as ‘it’s that time of the month,’ ‘female troubles,’ ‘sickness,’ and countless others. Just living in the 21st century and still facing problems with normalizing menstruation is a big setback for global development and female empowerment.

Recently, a short documentary, Period. End of Sentence by Rayka Zehtabchi won the hearts of many Netflix users around the world and won the Oscar for Best Documentary (Short) at this year’s Academy Awards. “I’m not crying because I’m on my period or anything. I can’t believe a film about menstruation just won an Oscar,” Zehtabchi said. The documentary showcases various obstacles that come with the deeply rooted stigma around menstruation especially in low-income families. In a rural village in India, for generations, women didn’t have access to menstrual pads and were forced to use dirty fabrics like a gauge to clean themselves, leading to many health problems. As soon as girls started their period they began skipping school or dropping out altogether. The ongoing stigma deprived many young girls from reaching their dreams and aspirations. Zehtabchi installed a menstrual pad dispenser in the village, made pads with women who had never worked before and successfully distributed them among other women within the village. The group of women who participated in this initiative with Zehtabchi named their brand FLY because they want women to soar.

Throughout the documentary, Zehtabchi presents a series of interviews, of both men and women, addressing the problems surrounding menstruation in society. The documentary starts with two girls in their adolescent years who are extremely shy and hesitate to speak when they are asked about menstruation. Other women also spoke out about their long and uncomfortable walks through the farmlands during the night to dispose of used menstrual cloths and also the religious beliefs that restrict them from worshipping during their period. Things get even worse as they also address their feelings of embarrassment and public humiliation when their dirty clothes are brought back to the streets by dogs and other stray animals. At the same time, the interviews show a sneak-peek of confused men who know very little about menstruation and were not supportive in the making of menstrual pads. This stigma was also further elaborated on in the documentary by introducing Arunachalam Muruganantham, the ‘Padman’ of India, who created low-cost sanitary napkin machines for women in the villages to make their own pads. Muruganantham addresses menstruation as the “biggest taboo in India.”

This narrative of Indian women learning how to manufacture sanitary pads for themselves is an incredible example of the movement for destigmatizing menstruation and empowering women. This would not have been possible without the leadership of high school girls in California, who initially raised the money for the dispenser in rural India and began a non-profit initiative called The Pad Project. Initiatives like these should become more prevalent around the world, especially ones that target less fortunate women who are keen to learn and become self-sufficient, but lack the resources to do so. Through advocating for female empowerment, increasing education on healthcare, providing resources and encouraging conversations surrounding women’s health, not only will we hopefully eradicate the taboo surrounding menstruation, but we will also be able to celebrate it for the natural experience that it is.

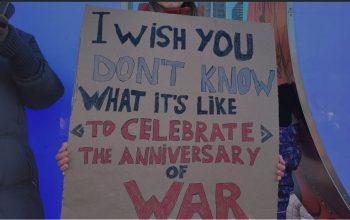

Statistics show that more than 137,700 of girls in the United Kingdom missed school in 2017 because they couldn’t afford menstrual products. Reports also suggest that girls in the U.K. are reportedly putting their health at risk by using menstrual products for longer than they are supposed to. The general unaffordability of menstrual products has played an unchanging role in hindering the efforts to destigmatize women’s periods. It is crucial for this to come to an end. Sanitary pads and tampons should be free for all women. They are in no way a “luxury.” They are everyday necessities. Governments should look closely into publicly funding menstrual products for women who are unable to afford them and provide them with good quality resources. This initiative will definitely put into motion an end to this stigma as I completely agree with the filmmaker Melissa Berton when she says, “A period should end a sentence, not a girl’s education.”