Photo Credit: Scott Gorman

A night at Hart House Theatre

Korto Zambeli-Tardif, The Mike Staff Writer

The Canadian identity is deeply idiosyncratic. I say this as an educator. As I leaf through textbooks and policy documents, one of the questions that keeps grabbing me is this: Why is Canadian identity still so wrapped up in the British experience of World War I?

Of course, the Canadian Expeditionary Force (later the Canadian Corps) was an imperial subdivision of the British Expeditionary Force. It’s true that Canadian soldiers were legally British. But now, a century later, Canadians are descended from people touched by the war in many different ways. Yet the memory of naive Tommies, trapped in the trenches for four muddy, bloody years, persists.

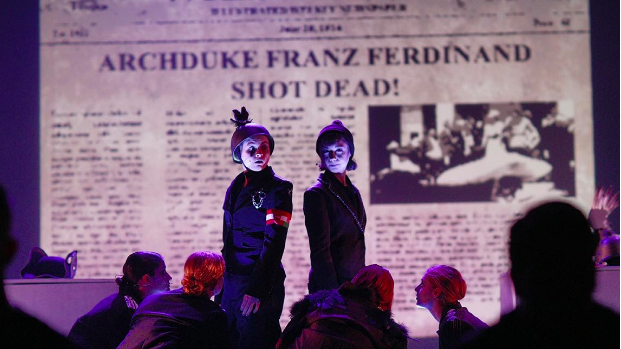

Maybe this is why Hart House’s production of Oh, What a Lovely War! feels so familiar. It starts with the same kind of political cartoon used by Canadian history teachers to convey the European theatre in 1914. Six women wearing silly hats speak in sillier accents, standing in for the rulers of the competing European empires. So far, the Hart House production conforms to the Brechtian alienation from specific characterization used by the show’s original production by London’s Theatre Workshop in 1963.

Much like previous productions of Oh, What a Lovely War!, Hart House’s imagining jumps from pastiche to pastiche of famous scenes from (Britain’s) Great War: the Christmas Truce, the slaughter of the Somme, Mons, the digging of trenches. The piece is strung together with popular British songs of the early 20th century, all of them joyful tunes with gory and bellicose lyrics. This play is very British: the recruits through whose eyes we see snapshots of the Western Front are a gaggle of working class lads from across the British Isles.

Behind the iconic moments lies a sinister link to more modern violence. The seven actresses are credited in the program as “Avatars.” The six male actors are credited as “Players,” and they begin the play not as Tommies but as modern-day dude-bros, perched on the edge of the stage with gaming consoles in hand. A giant green head is projected onto floor-to-ceiling screens to announce the Great War’s progression just like the interface of a retro video game. The female Avatars draw the male Players into World War I by seductively strutting forward, proffering Virtual Reality headsets.

This framing device is the original contribution of director Autumn Smith to Oh, What a Lovely War! World War I is firstly portrayed as a never-ending cycle of death and resurrection, the “Players” never allowed rest or respite. Secondly, there is the spectre of male gamers who are sequestered in a parasocial environment of idealized feminine avatars and hateful rhetoric. The modern reality of online radicalization is never quite articulated, but it doesn’t have to be. It is enough that the link is made.

For two hours, the Players and the audience are fully immersed, as every cast member dons a series of emblematic identities but returns time and again to the status of infantry soldier, stuck in the muck and gleefully singing another gloomy wartime tune as they march toward death. Not to say that Oh, What a Lovely War! is depressing. Indeed, between the bawdy singing and the impressionistic recreations of childlike games, it’s quite funny.

It’s also invigorating; on the opening night of Friday, February 28, the cast earned several ovations for some impressive athletics that illustrated British troops’ strict training regimen. The play’s video game conceit is clever, but it is during the sequences of physical action that the company really shines. The show’s choreographer is not singled out in the program, but director Smith deserves many accolades for crafting a show where every physical talent in her cast is proudly displayed.

Oh, What a Lovely War! has always been a show in which the disastrous folly of the Great War is juxtaposed with the self-deprecating pluckiness of British pop culture. Yet as I said, Smith and company have injected a darker strain of contemporary anxieties into the mix. The boys pull off their VR headsets and breathe a sigh of relief. War is over. Or maybe not. The ladies lean forward simultaneously, each whispering into one man’s ear: “Play again.”

It’s a chilling coup de grâce for a play that often seems to be labouring over some very rote history. That final, very abrupt tableau is worth the price of admission, and all of my misgivings about Canada’s exclusive obsession with trenches are forgotten in the face of the truth. Canadians need to keep perseverating over the War to End All Wars, because War did not end at all.