Photo Credit: Samantha Hamilton, Photos Editor

An Account of Differing Visions of What Politics Represents and the Relation it has to Faith.

Jonas Cardenas, Logos Editor

The activity of politics has been around for humanity since time immemorial. As human beings, we always saw the need to live and work together; to create communities and form whole scale societies to fulfill our material and transcendental needs. Classical notions of politics describe it as one of the highest expressions of human life. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle classified human beings as “political animals,” our humanity consisting of faculties of speech and reason enabling us to cooperate and produce great things. Keeping with the vision that politics is a creative endeavour, the notion of man as a political animal can find coherence within broader religious frameworks. This article will make that consideration from a primarily Judeo-Christian lens. From the beginning of scripture, God’s first request to human beings was that they “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth” (Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition, Gen. 1:28). In a certain sense, the vocation of humanity contains a political aspect, being co-creators with God in shaping the world around them and cultivating the true, good, and beautiful in everyday life.

In contrast to the classical notion of what politics represent, a dominant opinion of modernity sees politics as an alienating feature of society, a point of contention and controversy between peers and a possible catalyst for headaches at a dinner table. Images of Machiavellian politicians, bureaucrats, and high-standing officials are constantly portrayed in pop culture. Scheming, manipulation, corruption, scandals, propaganda, powerful rhetoric, and broken promises paint the pessimistic portrait that we might associate with political activity. Rather than politics and political science being “the most authoritative science, the highest master science,” according to Aristotle, or the science which can lead us to a form of happiness, politics is instead viewed as a necessary evil leading us toward achieving our collective goals as a society. Perhaps we would prefer the state to have less interference in our daily life, and that we are better off minding our own affairs than having institutions arbitrarily affect us. Perhaps we desire a private happiness that is untrammelled by the obligations we are demanded or expected to fulfill by political authorities.

Coming out of a recent Canadian federal election, why is the question of what politics represents important as human beings and persons of faith? One way of responding to the question is to approach it from the lens of human nature. From the beginning of humanity’s existence, man is made in the Image and likeness of God, given an eternal soul and a free will to choose and act (Gen. 1:26). Since our souls are made from eternal nature, nothing finite will completely satisfy the soul.

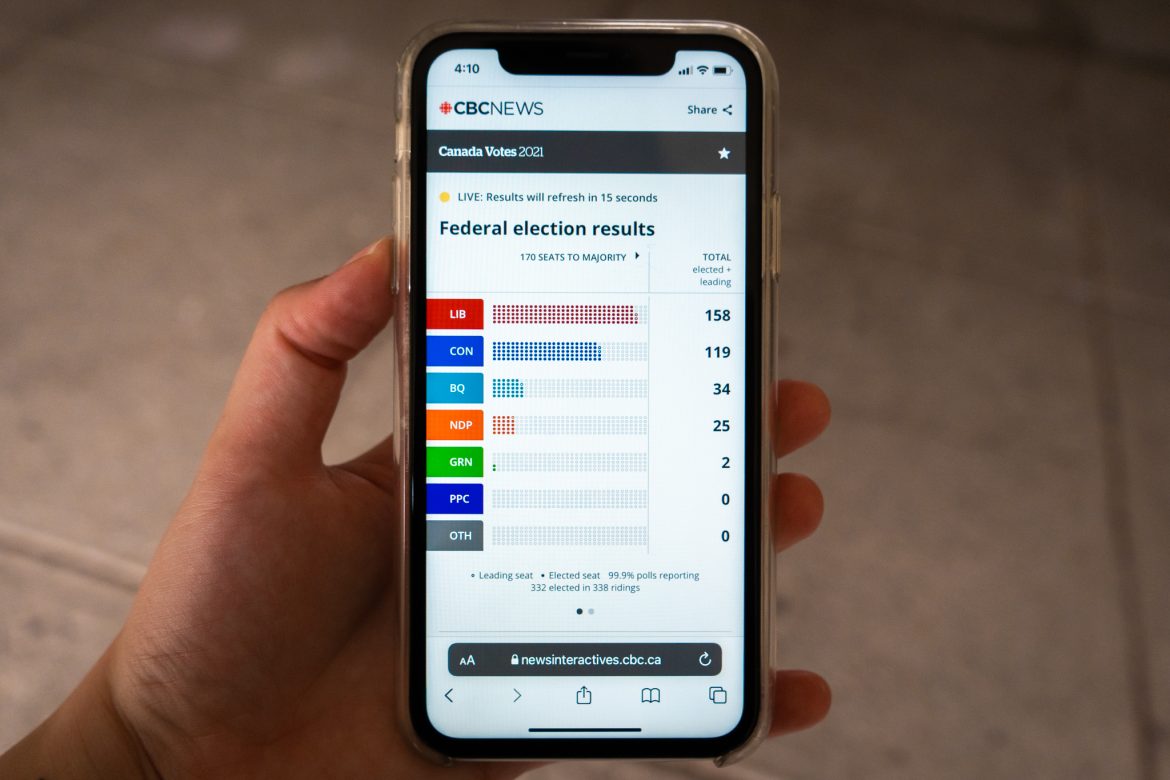

Family, friendship, pleasure, honours, and the various achievements we have do give meaning to our lives in a certain sense, but as incarnate souls we seek for more; searching and attempting to find what ultimately gives us fulfillment. With the results of the recent election, people feel a diversity of emotions. If we devote so much of our time to such activities in politics, whether it be tracking results, following charismatic leaders, etc., we will inevitably feel frustrated. Indeed, there is a dangerous possibility that too much devotion and loyalty to a person and party can transform a personality or sociopolitical group into a false messiah or cult that dominates every feeling, thought, and action we have. The twentieth century demonstrates this principle well, with the dominance of communist, fascist, and Nazi ideologies and dictatorships reshaping their societies into their own fantasies, taking away freedoms and destroying the sanctity of human life across the world.

To the Herodians, Jesus said, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (RSVCE, Mt. 22:21). Political sovereignty is not mutually exclusive to the ultimate sovereignty that God has over creation. But we would do well to make a clear distinction between what we owe to each, especially in relation to our social and political persuasions, commitments, and loyalties, lest we mistake the things that are finite for the things that are eternal. If we become dubious and skeptical of the correct distinction between right and wrong, good and evil, there is danger of becoming Pontius Pilate in our own ways, questioning and deciding for ourselves “What is truth?” (RSVCE, Jn. 18:37-38) Moreover, as beings with free will, each person is a moral agent responsible for the choices and actions they carry out. The totality of our lives is imbued with a moral content that perhaps we do not immediately realize, but that will be inevitably judged at the end of time.

Consider the corporal works of mercy outlined in Matthew 25:31-36 and what their success and failure would mean. How we treat our fellow human beings and the forms of politics, institutions, and arrangements that are elevated and in place is an expression of what kind of society we have. As disciples and children of faith, we should desire a society that accords each and every human person with dignity and respect by virtue of the Imago Dei. We should desire a just society that corresponds to the highest truths and values given to us by the creator. If anything, we need hope to situate ourselves in our current social and political arrangements if any change and progress are to be done. Hope is not blind optimism, but a trust before God, working from his plan and on his time. It does not mean indifference to others and inaction in community space. Politics is the means by which we achieve the common good and pursue justice, freedom, peace, and other desirable conditions for human life. Anything greater we attribute to politics will inevitably leave us feeling empty and leading us to seek for more.