Photo Credit: networkingnerd.net

Investigating why high-achieving students still feel inadequate

Taylor Medeiros, Features Editor

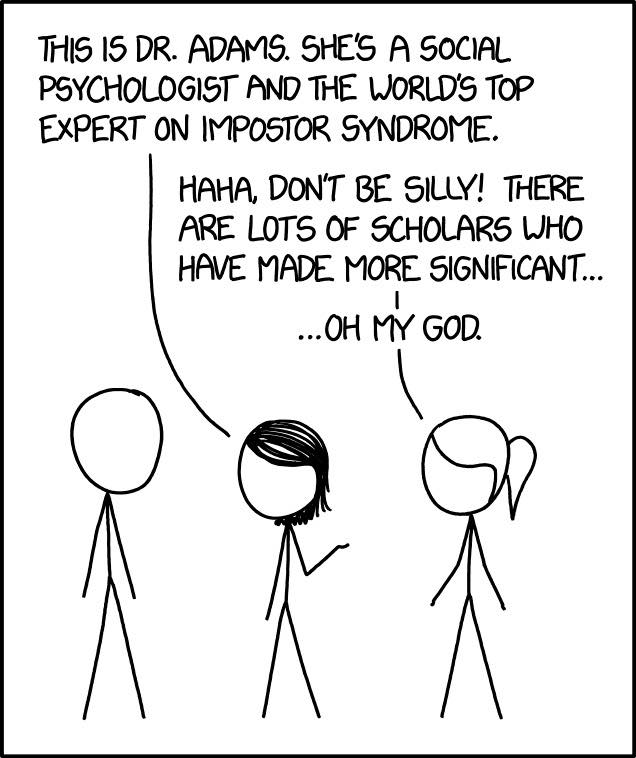

Approximately 70% of people have suffered from imposter syndrome. Harvard Business Review (HBR) defines imposter syndrome as a collection of feelings of inadequacy, despite evident success. Those who consider themselves “imposters” tend to suffer from persistent self-doubt. Even if there’s proof of their academic achievements, “imposters” feel that they have “intellectual fraudulence,” which crushes any sense of success. They have a hard time accepting their accomplishments, no matter how successful they really are. They discount any praise they receive because they believe they don’t truly deserve it.

Further, HBR gives insight to research which suggests that imposter syndrome is common amongst those who consider themselves perfectionists. This research also suggests that imposter syndrome is especially linked to perfectionism in women and academics. Imposter syndrome has also been linked to depression in teens and adults.

According to Forbes, imposter syndrome can affect those of all ages. Where, then, are the common links? In the 1980s, Dr. Pauline Rose Clance, the first doctor to research imposter syndrome, spoke to suffering adults and deduced that the way their parents spoke to them as children was the initiating factor. Parents who continually criticize their children create an unattainable standard of success. This follows their children into high school, post-secondary school, and adulthood.

On the other hand, Clance suggested that adults whose parents praised them as children, also suffered. When parents say non-specific, superlative things about their children, they are creating impossible ideals. For example, students who grew up hearing, “You are the best at math!” end up realizing that they’re not “the best” at math, but still feel pressured to pursue the subject to fulfill their parents’ expectations. Similarly, students whose parents made the comment, “You can do anything you want to do,” may have realized that they cannot “do anything,” and ultimately felt ashamed.

Imposter syndrome often has irreversible effects. For example, students may pursue an “easier” program or job that they know they can do perfectly, rather than a more difficult job with potential for making mistakes. Psychology Today states that perfectionists often turn into low performers for this reason.

The Muse offers five “types” of imposter syndrome which a student can identify with:

The most common type, “The Perfectionist,” micromanages, has difficulty delegating, accuses themself of “not being good enough for the job”, and feels like their work has to be perfect all of the time.

The second type, “The Superperson,” stays later at work than their peers, gets stressed when they’re not working, leaves hobbies to pursue more work, and feels like they haven’t earned their title.

The third type, “The Natural Genius,” is accustomed to excelling without a lot of effort, has a track record of doing exceptionally well, was frequently told that they were “the smart one” while growing up, dislikes having a mentor because they believe that they can figure out anything, is discouraged easily when faced with setbacks, and avoids challenges out of their comfort zone.

The fourth type, “The Soloist,” feels like they need to accomplish jobs on their own and puts their projects’ needs above their own.

The final type, “The Expert,” shies away from applying for jobs unless they meet every academic requirement, constantly seeks out training and certifications because they feel the need to improve their skills, always feels like they “don’t know enough,” and shies away from being called an expert.

Imposter syndrome doesn’t specifically affect those with low self-esteem or a lack of self-confidence. Those who suffer include high-achieving and highly successful individuals. This allows the questions: Who feels like this? Under what circumstances? Are there commonalities amongst those who suffer?

The Mike interviewed two current students and one recent grad and all three individuals identified with having imposter syndrome throughout their years at the University of Toronto (U of T), despite being in different programs. The interviews have been shortened for clarity.

The Mike asked Student A, a fifth-year student who identified with being the “Superperson,” “Soloist,” and “Natural Genius,” why they feel like an imposter. They stated, “I find myself primarily feeling like an imposter with school. I used to be one of the smartest — the top dog — and through my time at U of T, I’ve realized that I’m less than. There are several people who are far better than me.” They further articulated, “I notice that I am always putting on a face that I am smart and I can do it but I really am not. Especially since I lost my direct route with school and took more time, it really makes me feel off.”

When The Mike asked Student A what a “successful” person looked like, they expressed, “[Successful people] rarely crack under pressure. They are extremely supportive and always willing to lend a hand despite their own workload. They consistently exceed expectations.” Upon being asked if they “fake it ‘til they make it,” Student A admitted, “100%. I find myself so scared to ask for help or support even though I should. In a lot of classes, I know I am confused and could easily ask for help but the judgement makes it so discouraging.”

The Mike asked Student B, a third-year student who identified with being a “Perfectionist” and “Soloist,” why they felt like an imposter. They said, “I generally feel like an imposter whenever I participate in anything at U of T, specifically during tutorials. I tend to feel like an imposter during any kind of leadership opportunity as well, which could be leading a presentation or working as an orientation leader.” They further explained, “I typically feel like I don’t know what to say in comparison to my peers in class. They seem to have all of these insightful thoughts that I would never even dream of having. They have the guts to talk in class and somehow have their TA understand and support their points. As for leadership situations, it always feels like I’m not qualified to be there. I tend to think that I have no clue what I’m doing even if outwardly it seems all okay.”

When asked what a “successful person” looks like, Student B disclosed, “When I think about someone in a similar situation as me who is successful, I think about a person who seems to be calm under pressure. This person is always ahead in their school work, yet manages to keep a social life. All of their assignments are handed in on time, and they still manage to go to classes and look their best.” After being asked if they “fake it ‘til they make it,” Student B admitted, “I constantly feel like I’m just ‘faking it ‘til I make it.’ I always pretend to understand course material even if I don’t. I lie to myself and my peers that I’m understanding all of my work. But I’ve been doing this type of thing for my entire university career and my 4.0 GPA is still not in sight.”

Finally, Student C, a recent U of T graduate who identified with all five types of imposter syndrome, stated, “Going into grad school in January, I still get the feelings of imposter syndrome because I think, ‘Should I be here? Am I as good as these other people in the program/the lab? Will I fit in with them? Am I on the same page?’ A lot of the feelings of imposter syndrome stem (in my case) from talking to other people and seeing what they’re doing and thinking, ‘Wow, they’re doing this and that and volunteering and working at this lab, and all these things’ and I’m only doing a fraction of that, should I be doing that too? Am I not doing enough?’”

Student C’s opinion of what a “successful person” looks like includes “the confidence they have and how put together they seem when they’re talking about what they’re doing. Usually it seems like they’re doing so much better than you/more than you to be successful in what they’re doing. Usually they seem to know what the next steps for them are as well so I tend to idolize the fact that they know what they’re doing next, they have plans. Some people seem to have everything figured out and are calm and collected about what they’re doing. It seems like they’re not stressing at all, and they have the perfect answer for things.” When asked if they “fake it ‘til they make it,” Student C said, “Sometimes I feel like I’m ‘faking it ’til I make it’ but other times I see things more positively. It’s difficult to tell yourself that your time will come and just because something didn’t happen at the same time as others doesn’t mean that it’ll never happen for you. Although sometimes it feels like I’m stepping into something I’m not prepared for and then those feelings of ‘fake it ’til I make it’ are super strong.”

The Mike asked each student additional questions about how their parents reacted to their successes while they were growing up (either with empty praise or with criticism, as per Clance’s research). Student A revealed, “It was a lot of hot and cold. [They] would go from, ‘You need to do better and this isn’t enough.’ If I got 95, it was, ‘Where was the other 5?’ But in front of other people, it was, ‘She can do anything, she’s so smart.’”

Student B told The Mike, “My parents were definitely the type to critique everything I did even if it was praised by everyone else. If I drew a really good picture that I got a perfect mark on, my dad wouldn’t even compliment it. He would just critique it and tell me what was wrong with it.”

Student C confessed, “They leaned to the criticism side. For example, if I didn’t get a certain mark that they thought was ‘good enough’ on a test, they would say, ‘Oh, what happened?’ I don’t remember hearing frequently that I made my parents proud. [Even] when I graduated university, I don’t think they said, ‘We’re proud of you.’ Maybe, ‘Congrats,’ or something like that, but I felt like I was always struggling for their approval.”

Each student revealed that they were potentially affected by the comments their parents made in their childhoods, and still make currently. These interviews bolster the claims made in Dr. Clance’s studies.

Parents can help prevent imposter syndrome. According to Psychology Today, Clance said, “I think it is so important to look at what [kids are] doing well, and to listen to what they think they’re doing well. And then to listen to what’s hard for them, too. You know, begin to help them get a more realistic picture of what they can and can’t do, with encouragement. But not saying, ‘You can do anything you want.’ I would have them have the child begin to think about: ‘What do I do well? What do I have trouble with? What can I do to improve something that I have trouble with?’ Or at least get it good enough.” This is transferable to university campuses, too. Students can support each other without putting pressure on their peers.

The University of Toronto is infamous for having a “rigid” and competitive environment. This leaves students struggling to feel like they’re “good enough,” and struggling to fit in. As a student population, we can help those who are struggling by using specific words of encouragement, instead of empty praises. It’s important to say, “You were accepted! You belong! You deserve to be here just as much as I do!” because every student deserves to feel like they belong, and that they’re doing the best that they can.