Photo Credit: RhondaK Native Florida Folk Artist

Students in creative disciplines are receiving ‘passion pay’ in lieu of a real salary

Isabel Armiento, Editor-in-Chief

A knowing nod, a pseudo-sympathetic smile, and then some well-meaning pedantry: “Well the problem is, you’re going to have to choose between making money and doing what you love.”

If you’re someone working in the arts, you likely get this unsolicited advice almost every time you admit your career goals. Yet while aspiring creative types are expected to “choose between making money and doing what they love,” someone whose passion lies in, say, computer programming is never told to sacrifice their dream job for the sake of money.

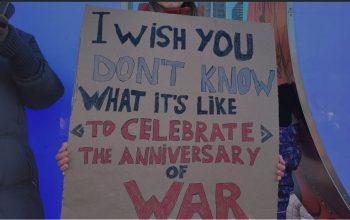

It is a well-known fact that creatives — people pursuing at least vaguely artistic work — are paid less. In this way, passion becomes a kind of quasi-currency, and future creatives are warned against choosing a career in which passion is a substitute for a stable salary. This phenomenon — where money is replaced by the pseudo-currency of passion — has been bitterly labelled “passion pay” by youth who undertake creative work that lacks any compensation other than the supposed joy of the work itself.

This expectation that creative work will beget jobs only aggravates the problem of passion pay. There is a cultural push toward seeking self-actualization through work — a myth fueled by a paradoxical desire for both hyper-productivity and fulfilment. Creative work thus ought to be demystified — contrary to popular belief, it is not all passion and thunder, and a job in the arts often looks awfully similar to a conventional office job.

Passion pay is an epidemic in the creative industries, where free labour in the form of an unpaid internship is a rite of passage. Unpaid internships aren’t legal in Ontario, but that doesn’t mean they don’t happen — and they are often veiled under the benevolent guise of education. A cursory search through Indeed will reveal a myriad of job listings that cite course credit as the only payment offered for essentially full-time work. In fact, I searched “editorial internships in Toronto” on Indeed and the results were harrowing: of the first 10 position listings, nine were unpaid.

***

As a dedicated logophile with absolutely no other ambition than to read and write as often as possible, I knew that to get into a word-based industry — whether writing, editing, or publishing — I was going to need to do some unpaid labour. I traded my time and talent for some cushy resume padding and the title of “editorial assistant” at a nebulous company, working without pay for several months. I wrote copy for a men’s lifestyle magazine, researched and curated ideas for the next spread, catalogued product information and press emails, copy-edited absolutely everything, and ran a soul-sucking social media account aimed at aging women who ostensibly wanted to live forever. Needless to say, the “passion pay” I received as compensation for many hours of labour was unsatisfactory — the work I did was often menial, and never meaningful.

Despite being exploitative (and illegal), this sort of editorial assistantship is expected of burgeoning writers — so much so that companies can easily replace paid labour with unpaid students desperate for experience and exposure. I was ‘working’ with a staff entirely composed of talented (but unpaid) interns, covering everything from graphic design to writing to social media to marketing to website creation. I interned for a company that was essentially funded by young people’s passion, proving that passion perhaps is a valuable currency. My creativity wasn’t so valuable that I could exchange it for money, yet it was valuable enough for the company to market, sell, and profit on.

***

Passion is not a sufficient salary and exploitation should not be the norm. Yet, as I spoke to some peers, I realized that it has become increasingly normalized. Fasai, 23 is a graphic designer who recounted her experiences as an undervalued, unpaid labourer. She told The Mike, “When I started my art career after university, I did free or heavily discounted studio work in exchange for professional experience. I gained invaluable skills — but it definitely didn’t offer any better [experience] than paying jobs.”

Her frustration with this experience was compounded by the fact that her work could so easily be discarded – precisely because it hadn’t cost her employer anything. “No matter how much time and effort I put into my work it had no value to my bosses because it was free. [This meant that] projects could easily be thrown out the window and the artist just wasted their time.”

Kyle*, 20, is an architecture student who recounted his experience ‘working’ for Lululemon without pay to fulfil a course credit. He helped design and construct “a wheelchair accessible meditation pavilion… with a capacity to seat 2–4 people at a time,” an opportunity that he appreciated and was grateful for despite the lack of compensation. The team of unpaid interns worked diligently to create a “fabric/metal screen [that] was built to come apart as well as the main unit (which could split into half) for easier transportation potential.” It was labour- and time-intensive; “The whole process took full days and long hours over only a fast-paced two-week timeline,” Kyle told The Mike.

While these unpaid internships were part-time or contract work, others can be all-encompassing. Nikki*, 25, worked full-time — nine to five, Monday to Friday — as an intern at a publishing house for a total of nine months. While she was compensated, the amount was negligible. She told The Mike, “After 3 months I got $1,000. I went back with them for another six months and I got paid a bit more but it was still not a lot.”

While she enjoyed some aspects of her work, the majority of it was menial and certainly nothing that could qualify as ‘passion pay.’ “I’d make coffee and run errands and stuff… I’d say mostly assistant [work] day to day,” Nikki told The Mike. “My role in my contract was assistant. I handled scanning documents and filing when needed, answering the phone, I kept records of receipts, submissions, and mail (in and out of the office) in spreadsheets.”

She explained that there was “also a bit of meaningful work,” citing publishing events and book launches she got to attend as unexpected perks. Some of the work was relevant to her vocation — but it certainly wasn’t all driven by passion. “We would get manuscript submissions and [for] the ones my boss would want to know more about, I would reach out for the full manuscript, read it, and write up a brief report about my thoughts… and a bit of summary. I also collected media on author/books and put together publicity packets a couple times,” Nikki recalled.

During her internship Nikki was working toward a publishing certificate and told The Mike that while internships aren’t necessary for her program, they are an “added bonus” and “most [students] get at least one internship during [their] studies.” Unpaid labour is thus not only an unfair expectation but actually sought after, and even exclusive; unpaid editorial and artistic internships with top companies are highly competitive and demanding. Conversely, tech internships are paid, and lavishly. Interns at Snapchat are paid $10,000 a month and interns at Apple, Google, and Facebook — as well as startups like Slack or Quora — could be looking at yearly salaries in the six figures. For comparison, internships at Vogue, the editorial equivalent of these tech goliaths, are just as sought-after yet completely unpaid.

***

A research paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology unpacks the reasons behind the ubiquity of passion pay. The study found that participants were more willing to ask passionate workers to make sacrifices for their job, such as working extra hours with no pay. This mindset normalizes the practice of passion pay as an acceptable, viable, and even sought-after currency.

Somehow it is seen as fair to exploit someone who loves their job — an assumption that extends across all creative industries but abruptly stops with historically “practical” fields such as medicine or engineering. This discrepancy stems from a wildly fallacious belief that creatives love their work so much that they would be slogging away at it in their free time anyway — rather than hanging out with friends, watching Netflix, or reading a book.

An article in Monster muses over doing what you love versus doing what pays, reifying a dichotomy between these ideas without exploring the nuance behind it: why should loving your work devalue it? This dichotomy is imagined as a simple equation in which the more enjoyable your work is, the less salable it becomes. Related articles function as how-to guides: how to make money doing what you love, how to translate passion currency into Canadian dollars. This whole conundrum simply doesn’t make sense; creativity is at the apex of Bloom’s Taxonomy and is an undisputedly valuable work skill — so why is it treated like the antithesis of productivity?

Creative work shouldn’t be an object of compromise or sacrifice, but rather given its due authority as a viable career. Alternatives such as passion pay or bifurcation — those with a traditional, lucrative nine-to-five who pursue their creative passion as a side hustle — should not be the only avenues for pursuing necessary creative work. We need to dismantle the binary between work as passion and work as a way to pay the bills and acknowledge and appreciate that no one — not even creatives — will be fulfilled by work alone. Enjoying your work is not a sin worthy of lower pay.

***

Passion pay makes creative work exclusive — and even classist. An article published in 2018 cited 86% of internships in the UK as unpaid — a statistic of no small import given that internships are basically a prerequisite for entry into creative industries. Creative freelancers suffer similar monetary sacrifices. A study found they lose over CAN$10,000 through taking on unpaid labour that they feel compelled to do for a host of reasons: they feel unable to say no, need to further their career, want the exposure, or are regarded as unqualified to ask for money in exchange for their creative services. Being creative — even professionally so — has become expensive.

This means that those who can afford to undertake these internships usually are supported by a family who can afford to sponsor them. Those with golden tickets into the creative streams — where the ‘golden tickets’ are unpaid internships and freelance work — are thus usually wealthy. This financial barrier establishes creative work as an inherently privileged, even frivolous field and reinforces stereotypes of creative work as cushy and luxurious. Passion pay perpetuates a cycle in which wealth is necessary for the privilege of being creative — making creativity synonymous with entitlement and a lazy ennui.

Class isn’t the only way passion pay caters to the privileged; it is also potentially sexist. Women tend toward creative vocations while men tend toward STEM, thus privileging traditionally masculine passions as more valuable and financially sustainable than feminine passions. Compounding this is the tendency of women to be risk-averse, in part because they are so often burdened with the role of primary caregiver for children and the elderly. This means that the few highly-paid creatives — those with the biggest payoff to their requisite monetary sacrifices — are often men. Men may occupy the spaces of both the statistically most creative members of society and the least — which means that they reap the scarce benefits of creative employ while making fewer sacrifices and suffering fewer fiscal consequences than women to pursue their passions. For men, therefore, passion pay might be better compensation — both because creative men literally make more money, and because men following traditionally masculine passions get paid better.

***

According to an article in The Guardian, “There’s a culture in the creative industries that allows unpaid work to go on far too long and take over responsibilities that should be reserved for paid staff. Yes, people will do it, but that doesn’t mean it’s right or productive.” Unpaid creative interns are often performing the same labour as other, paid workers — and thus are being ‘paid’ in passion for their labour. It is a cycle that will not be broken as long as internships and freelance work are required for entry into the creative industries — and as long as companies are willing to exploit young creatives’ desperation (and yes, passion) to save money.

Passion pay turns love into a physical currency. It assumes that no one should be paid to do what they love because passion is pay enough — unless what they love translates into a practical job such as professor, manager, doctor, and so on. An article in Forbes reminds us that, “In theory, yes, creatives are driven by internal love of the work. But in the real (aka corporate) world, the work isn’t always meaningful.”

Despite all this, I still haven’t fully divorced from the world of creative unpaid labour. Currently, I do a bit of free work for a literary journal, sorting through the slush pile of creative writing submissions. Last quarter my stipend for reading, assessing, and commenting on hundreds of stories was only CAN$65. This time, however, my supplementary passion-pay cheque didn’t bounce: unlike writing uppity blurbs about menswear (as I did during my former unpaid editorial internship), creative writing is something I’m passionate about.

*Name has been changed.