Illustration Credit: Visual Generation, Adobe Stock

Self-reflections on the side effects of social media during the pandemic and problems with amplifying ideals of hyper-productivity

Chiara Greco, Editor-in-Chief

The internet screams, “you can’t just sit around and do nothing for all these months! Sure there’s a global pandemic going on but that doesn’t mean you can just stop being productive, you can’t just be lazy.” Well, actually I can. You see, the internet has this funny way about it; it seems to make you feel guilty for taking care of yourself.

When the world was struck with a global pandemic causing Canadians to go into lockdown and quarantine in mid-March our lives inevitably went through extreme turmoil, change, and for some trauma. Though, it would be remiss to not start this discussion by acknowledging the privilege this discourse has. The COVID-19 pandemic, to put it bluntly, has immensely changed the lives of quite literally everyone on a global scale. While this article will not be discussing the great loss, trauma, and fear this pandemic has brought about, it seems wrong not to at least acknowledge it before taking on a bit of a lighter debate.

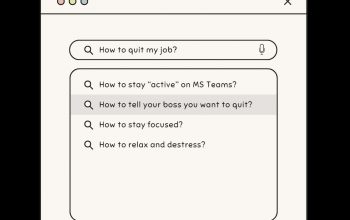

Now, while I cannot speak for everyone here, I can generally say that most people’s lives have gone through immense change. Nearly all of this change has been plastered across social media in ways which perpetuate some rather unkind trends. The language social media uses and has used to speak about the pandemic and our role in being ‘normal’ or productive during it has had some rough side-effects. Social media has illustrated this time in lockdown as ‘time off.’ Or as a chance to finally be productive with no worries of work or school deadlines. If we go even deeper, some social media platforms, such as Twitter, specifically have worked to establish a sort of capitalist notion of productivity, when in such a stressful time, people should be stepping back to relax and take a break. It seemed to me, at least, that when things started to go into lockdown, especially when businesses began to close, and schools shut down, people pushed for this idea of hyper-productivity; an idea that perpetuates the capitalist motto ‘you are what you do,’ or in other words, the idea that even though your workplace has closed, doesn’t mean you should just stop working.

At the beginning of my quarantine in mid-March and early April, this capitalistic idea that we all need to immediately be productive, to use this so-called ‘time off’ wisely, was constantly ringing in my ears. After all, Shakespeare wrote some of his best plays while he was in lockdown during the plague, so what’s stopping us? Well, to put it simply: a lot. I mean, our world today is immensely different from Shakespeare’s world when he apparently wrote King Lear or Macbeth. Our dependence on the internet has become like a little devil perched on our shoulders showing us all the people putting their time to ‘use’ while we sit and scroll through their ‘achievements.’ Sure, social media has always been this way, but the effect of amplifying ideals of hyper-productivity and self comparison seemed more apparent than ever. Each time I logged on, I’d be barraged with pictures and texts of people finally dusting off that old screenplay they never finished, or people preaching about the importance of remaining ‘busy.’ This narrative of the hyper-productive day, all while battling a global pandemic and uncertain future, seemed so far-fetched and harmful to me.

Hyper-productivity is not a new concept, and is definitely familiar to many students; it can be understood as the incessant need to always be busy. The hyper-productive day, quite like the capitalist’s day, does not allow for breaks or ‘time wasted.’ More often than not, hyper-productivity is damaging, leading to burnouts, another term students know all too well.

Within the constraints of our capitalist society, our productivity and ability to constantly be working and creating is deeply tied to our self-worth. While the COVID-19 pandemic seemingly presented a break to these constraints, social media immediately stepped up, making those taking time for themselves feel guilty when bombarded with posts of other people constantly being productive. All this to say, Twitter and other social media are structured to make the users feel bad about themselves. The best way to describe social media’s role here is to characterize it as a sort of guilt-trap. Let’s take myself, for example. Imagine I’ve just finished a two-hour online lecture, I’ve taken notes, I’ve worked on an essay, I’ve done my readings and I’m looking for a break. I open up my phone, I go on Twitter or Instagram, and I am immediately met with people pushing me to do more. I go on social media as a break from work but instead end up feeling lazy. It’s this exact scenario which normalizes burnouts. If all these people are always seemingly productive without rest, then what reason do I have to take a break? Herein the problem lies: more often than not, social media presents performative productivity. But, even if performative, this amplification of productivity, especially during a pandemic, is harmful.

In an article by the Washington Post, productivity expert Rachel Cook noted that during this time “there are a number of things working against the accomplishment of any task,” notably the shared trauma we are experiencing due to the pandemic. But, because we live under capitalist constraints of hyper-productivity, most people feel anxious by simply doing nothing. To this Cook notes that “anxiety and depression is up” because of the pandemic. Our current situation from Cook’s view is not “setting us up for high productivity or high performance.” But then why is it that social media seems to be continually perpetuating this ideal of hyper-productivity? I’d like to suggest that, from a social media standpoint, this productivity, as mentioned before, is simply performative.

By pushing even performative productivity during this time, we end up inevitably reducing ourselves and our abilities to purely economic value. Glorifying and amplifying ideals of hyper-productivity and ‘hustle culture’ are, as an article by The Guardian puts it, “part and parcel of late capitalism.” Taking a break is okay, especially in such unknown and distressful times. But with our identities becoming more and more defined by our jobs, our studies, and who we are to everyone online, this break seems more difficult. If we rest without reason we feel guilty, but if we don’t we seem to be projecting a false persona of ourselves, which personally, is far from reality.

With all this, it seems fair to say that the effects of social media and hyper-productivity have created many challenges to navigate during this time. Again, if I think back to my early experience of the pandemic, I was anxious with what was to come. I debated what I wanted to do,what I could accomplish during this time. To say I felt the pressure to do something would be an understatement. My brain was in a scramble trying to work out how to finish the 2020 school year while also trying to work out which projects to pursue in quarantine. But, I’ll admit that after being in lockdown since April and with June just around the corner, I reached a point of anger, or perhaps realization, with social media: just because others appear to be busy, does not mean I need to be. While it was difficult to do at first, halfway through the lockdown I accepted this and took rest without reason.

Speaking to other students, I noticed similar trends. When asked about his experience with productivity during the start of this pandemic, a student entering his third year noted that he “felt immense pressure and stress to just be busy.” He continued, “I was in the middle of studying and writing exams, but for some reason felt like I wasn’t doing enough, that I just needed to keep adding more onto my plate.” When asked whether or not he felt social media added to this stress he said, “it wasn’t just purely social media as it was just this ominous guilty feeling I had for not doing more, I think as students we put even more pressure on ourselves to always be busy, which becomes draining, and seeing others being busy tends to make us feel worse.”

From a completely opposite standpoint, a student who was working to finish her first year of university during the lockdown suggested that she had actually used productivity as a coping mechanism. She stated, “being busy or productive made me feel like I actually had control over my life during the lockdown.” She continued, “I can see how constantly pushing productivity can be harmful, but I used it to my own advantage and I managed to actually limit how I used social media during this time.” Others have also noted this use of productivity as a form of distraction during a time when we truly don’t know what will happen next. In this sense, this constant busyness we create for ourselves is also used as an escape from our reality. But, this shouldn’t take away from the harmful effects hyper-productivity can have on our mental well being. Reflecting on my experience, I know that productivity does have the potential to help us, but not when it is being glorified by social media to the point of burnout.

So, how do we redefine our boundaries with social media and recreate this ‘new normal’ we’ve all been so fixated on? Sure, we have a huge problem of pushing hyper-productivity until the point of burnout, but we didn’t need a global pandemic to tell us that. Perhaps, for me this acted as a push to re-define what productivity actually is. Our relationships with social media is vastly unhealthy and I’m sure that won’t change anytime soon. But it is through our re-imagination of these things that we can move to create a ‘new normal’ for ourselves. If there’s anything we have to remember, it’s that we’re living through a pandemic: there is no precedent set to tell us how to fix all this.