Information sharing technology, through the ages

Jiaxing Huang SCIENCE & TECH EDITOR

Photo: Layla Pereira-DaSilva / THE MIKE.

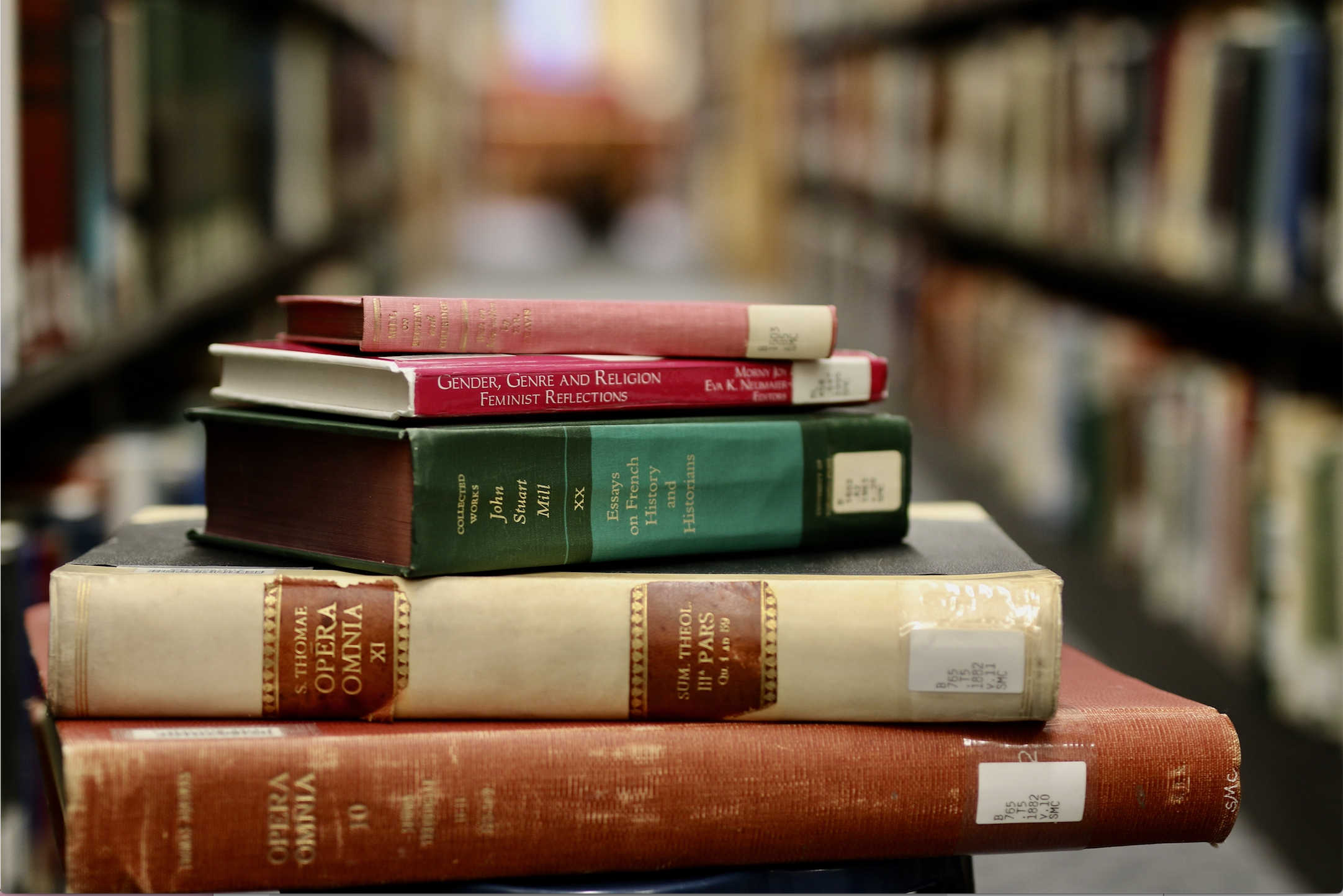

Of the seven colleges at the University of Toronto (U of T), The University of St. Michael’s College (USMC) is blessed to have the largest library. That’s right, I’m talking about the Kelly Library. Although, at first glance, many complain about the dull and boring neo-brutalist style in which it, like Robarts was built (Kelly in 1969; Robarts in 1973), there lies a completely different place inside, a world much more colourful and exciting: the world of books.

In this fast-paced, digital information era, my passion for books has puzzled my friends, many of whom view reading as a hobby that’s a little last century (after all, this is the internet age). And yet, I love my books more than anything else. For people like my friends, books seem like pretty common things. Not only do we buy textbooks (which grow more and more expensive with each passing year) for each new semester — there are also many public libraries and bookstores around Toronto where we can just grab a copy and start reading. Why should we spend any time thinking about such common, readily available things as books? In part, this is why some students would rather spend most of their time in Kelly Café than in the main library itself. Though you or they might not necessarily think so, this wasn’t always the case.

The history of books is long. It spans thousands of years. In fact, books, in various forms, have been in production since mankind first invented writing. The first books were most likely clay tablets produced by the Sumerians, who wrote with styluses. Styluses were made from various kinds of materials, but their uniting feature was that they each had a sharp point at the end, which would later evolve into something like the ball-point pen we use today. This is strange to consider given that, 3,000 years ago, it appears the Sumerians simply used styluses to write on soft clay before they baked it into clay tablets. Sometime afterward, the Egyptians invented papyrus, a thick paper-like material made from the papyrus plant that could be rolled up into scrolls and stored for long periods of time. From Egypt, papyrus spread to the rest of the Mediterranean region to places like Greece and Italy, where it was picked up by the Greeks and Romans for their own use. Between styluses and papyrus, it seems safe to say that back then, books and the instruments used to write them were quite different from the kinds we know today.

As a writing material, papyrus also has its disadvantages: one can only write on a single side of it, it does not allow for corrections, and it is made from the plant Cyperus papyrus that is native to Africa and cannot be found in other places. This is why, besides papyrus, the Romans also used wax tablets (known as Cerae in Latin) and parchment (from the hides of animals) for writing.

The main advantage of wax tablets is that if you recorded anything incorrectly the first time, the wax could be melted and reused again. Another advantage of wax tablets is that a bunch of them can be connected by strings to form a Codex — which eventually replaced scrolls and gave rise to modern books, in their more familiar form. The advantage of a Codex is that one can write on both sides of it, and it can be produced in most places as long as there are cattle and sheep. That is why, with the collapse of the Roman Empire, most regions in Europe gradually replaced papyrus with parchment and before the process of paper-making was transmitted to Europe, most books there were being created on parchment. In fact, U of T keeps many books written on parchment in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library inside Robarts, as does USMC’s own, Kelly Library.

Still, even parchment and wax tablets had their disadvantages. Parchment was very expensive to make, which is why, for a large part of their history, only the rich and noble could afford to have books. Wax tablets, although somewhat cheaper, were very heavy to carry around, and thus not suitable for long distance transportation. Only when the Chinese invented paper from plants were the two above problems finally resolved. In truth, the Chinese were the first civilization to pioneer printing. Only when printing was invented and popularized did books finally become a commodity accessible to most.

Together, paper and printing caused great changes everywhere, especially in Europe. The technology of papermaking reached Europe as early as 1085 in Toledo, and was firmly established in Xàtiva, Spain by 1150. France had a paper mill by 1190. Papermaking then spread further north with Germany in 1320, and in Nuremberg by 1390 in a mill set up by Ulman Stromer.

Then, around 1450, Johannes Gutenberg from Germany independently invented the printing press and printed the first book in Europe: “The Gutenberg Bible.” Gutenberg was the first to create his type pieces from an alloy of lead, tin, antimony, copper, and bismuth — the same components used today. From that point onward, printing spread across Europe, making books much cheaper, thus facilitating the widespread transmittance of knowledge across the populace. This also led to many key events in European history, not least of which were the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. Among other reasons, this is why the Gutenberg Press has been called by many the most important invention of the second millennium.

Besides the contribution from the advancements in writing materials, how books are organized and dispensed also contributed to the rise in literacy around the world. What I’m talking about more specifically was the establishment of an institution best known as the public library. Although the precursor to public libraries already existed in the classical period (see the Royal Library of Alexandria), they only become prominent in Europe following the Renaissance and in North America during the Industrial Revolution. One person was especially important in the development of public libraries in North America. That person was Andrew Carnegie. One of the richest people from the 19th to early 20th centuries, Carnegie made his fortune from steel production. However, before his death in 1919, he donated much of his wealth to charity work, especially toward establishing many public libraries (known as Carnegie libraries) across North America and the United Kingdom. In fact, there are a few Carnegie libraries here at Toronto, including the Koffler Student Centre — where the U of T bookstore is located — which previously served as the Central Public Library in Toronto. Establishing public libraries means that from that time onwards, books could be organized on an even higher level so that people could have a specific place to go for reading. This increased the speed by which knowledge could be dispersed significantly.

Nowadays, with the advancements in internet, internet technology (IT) giants such as Google are digitalizing books and are pushing for a worldwide open-source network so that people from across the globe can get copies of any books online. If this pursuit comes to fruition, which it appears likely to do, it will definitely cause another evolution in books because, although in the past, paper and printing have done a great job in the spreading books, there are still disadvantages to paper books, mainly because the raw material for paper making is plant fibre: this makes the mass production of paper damaging to our environment. Furthermore, while public libraries also contribute in spreading knowledge to the masses, building them requires money and not every place, especially developing countries, can afford the cost. This is where online open source comes in. Unlike traditional paper books, online books do not require the use of paper, and thus are more environmentally friendly. Also, online books do not require budgets to be allocated to build public libraries — people can just access any books anywhere, anytime, using only their computer, or even, smartphone.

With the abovementioned in mind, it becomes easy to see that the history of even such a common thing as a book is not as simple as it seems. What we now take for granted has evolved over thousands over years, alongside the materials used to create them. In fact, the history of books is closely tied with the history of writing material. Only when there are advancements in writing materials can new types of books be invented. One cannot imagine the existence of modern books without paper. Moreover, just like material, books have different levels of scales and organizations — from the simplest scroll, to a Codex made of many pages, to a library that contains thousands of books, to open-source networks that may soon contain millions of online books.