Photo Credit: Julliana Santos, Managing Editor

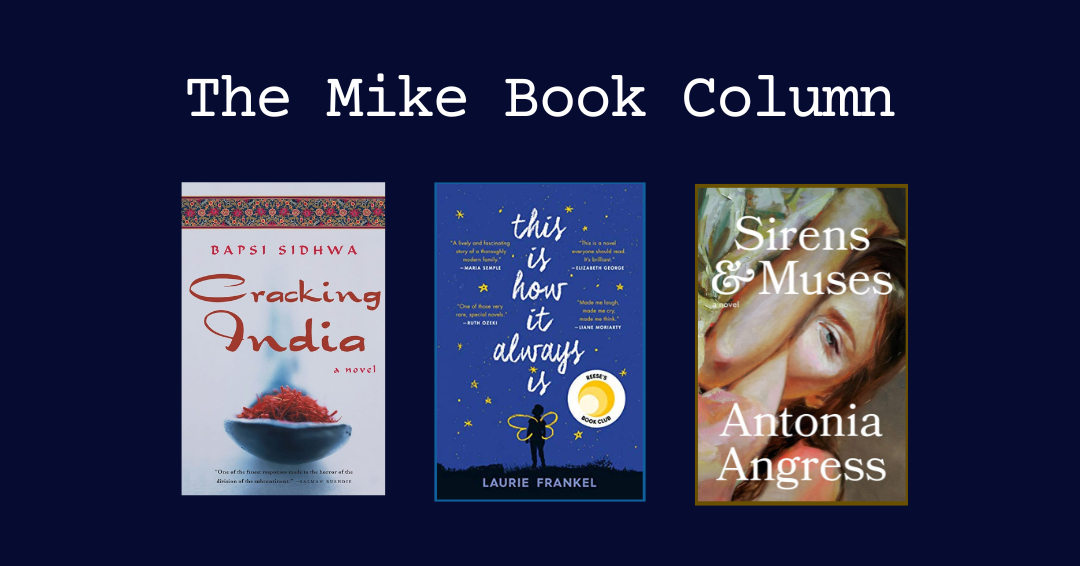

Sirens and Muses – by Antonia Angress

Agata Mociani, Associate Arts Editor

Antonia Angress’ recently published novel, Sirens and Muses (2022), revolves around two promising young painters whose lives intertwine after they begin rooming together at art school. Though academic settings have been a trend in literary fiction lately, Angress’ debut stands out through its understated plot and skilled characterization. Whereas many campus novels fall into genres like mystery or fantasy, Sirens and Muses is staunchly realistic in its depiction of contemporary college life, and its lack of complete resolution is a testament to this. One of my favourite aspects of this text is the author’s refusal to tie up loose ends neatly. Characters experience growth, but are still left wanting, questioning themselves, and wondering if they should have done things differently. They miss opportunities and leave things unsaid, and the book still ends.

Louisa and Karina are both forces to be reckoned with, and their living arrangement leads to a romantic entanglement that inspires both of them artistically. Though their relationship unfolds languidly (think: little touches, shared cigarettes, furtive glances), the young artists’ connection oozes tenderness and erotic urgency. The question is not whether the characters are in love, it’s whether their mutual desire can withstand friction caused by financial, cultural, and artistic differences. Despite their palpable, natural chemistry, there is a fierce juxtaposition in the ways Karina and Louisa conceptualize life.

Class plays a significant role in the narrative. The pretentiousness and privilege of the upper-class deuteragonist, Karina, is unpacked and examined closely. Louisa, who comes from a lower-middle class background, is not afforded the same opportunities, whether it be in the studio at school or in the highly exclusive world of artist networking. Unlike in many books that feature working class students fighting for recognition among wealthier peers, her financial problems are not magically solved through a deus ex machina. Instead, Angress highlights the difficult choices Louisa must resort to in order to pursue her passion.

One of the book’s only shortcomings is its inclusion of four points of view. Several chapters follow two lesser characters, both men, whose points of view are difficult to empathize with or even sit through. Despite my love for Angress’ writing style, I found myself skimming the chapters told from the perspectives of an edgy, entitled male student and his professor, an aging male artist who fears impending obsolescence. Even so, I found the author’s study of these characters to be nuanced. I just didn’t particularly care for them.

Had Sirens and Muses not captured the emotion of yearning so accurately, or had its writing style been less poetic, I might have not recommended it. After all, one doesn’t usually promote a book that features facets that annoy them. With this novel, though, the author’s beautiful writing style and meaningful cultural commentary outweigh the subplots that I disliked. The delicate, quiet love between Louisa and Karina is reason enough to read this book, as is their mutual, and complicated, passion for painting.

This is How it Always is — by Laurie Frankel

Julliana Santos, Managing Editor

In This is How it Always is, Laurie Frankel tells the story of a family consisting of two parents, five kids, and what Frankel calls a “secret that ends up keeping them.” The secret is this: the family’s youngest kid is queer. Queer, in the sense that no label can encompass the child’s experience with their gender identity — and no label should. Claude is five when he chooses to wear dresses and declares that he wants to be a fairy princess. Later, Claude goes by Poppy. She’s still five when she declares that she likes sundresses and wants to be an Ichthyologist.

Frankel’s comforting prose shows how two parents can love unwaveringly in the face of growing uncertainty. Not uncertainty about their child, but about the life that lies in their child’s present and future. The greatest strength of this novel is the way Frankel pays attention to narrative — how Penn tells stories to his kids before bed, mirroring their lives as they grow older, how the kids think of and rethink their futures, and how the entire family navigates neighbours, school, friendship, work, peer pressure, peanut butter, and all things families learn to deal with as they muddle through life together.

While Frankel’s tone may at times come off as too perfect, or too caught up in a “fairy-tale” way of storytelling, her intimate understanding of the intricacies of having a queer/trans/nonbinary kid shines through. She takes the reader through Rosie and Penn’s journey, as they try to plot the best course for their family in the face of societal pressures, discrimination, and feelings of fear rooted in concern for their child’s safety and security.

In the end, this is a story that needs to be told, and Frankel tells it in a way completely rooted in love and understanding. Unwaveringly so. If one can look past some points of too-well-worded-to-be-real dialogue, and a few too-neat-to-be-true points of the novel’s plot, one will find a story that truly takes the time to bring the reader through a process of transition, transformation, and (inevitably) constant love and acceptance in spaces that resist definition.

Cracking India — by Bapsi Sidhwa

Hamna Ashfaq, Contributor

This novel defines violence in all of its complicated forms that include the role of people and religions in the making and destroying of a nation and state. I read this book for a course and instantly realized its importance in highlighting an event that is almost always intertwined with cloudy judgment and stereotypical notions of victim-blaming and shady truths.

In this novel, Bapsi Sidhwa constructs the cracking world of India through the many aspects of its partition into two separate countries – India and Pakistan. Told from the voice of a polio-stricken, disabled, 8-year-old Parsee girl named Lenny, this novel deals with the complexity of divisions within the land, people, religions, and society. Lenny describes the way her world stands on a tipping scale of change, violence, and disruption as she grows and realizes the gravity of every action laid out in front of her. The role of gender, authorities, politics, religion, violence, and colonization highlight the world of Lenny as a place on the precipice of destruction.

The author explores the effects of the partition through its many stages within the Indian subcontinent. From the role of the abducted and displaced women who were objectified and taken as nothing more than property, a symbol of the nation-state. To the refugees, bloodshed, which was more like a genocide that impacted generations to come. To politics that changed the trajectory of people, land, and society within a land already empowered under power-influenced authorities. Among all these complex and deep themes, the novel works to narrate the life of a small girl who, while shielded from the truth, realizes the truth faster than most do in their lifetime. In her novel, Bapsi pushes the boundaries of fiction and reality as she masterfully paints a clear image of a horrid and aching world through the voice of a child.