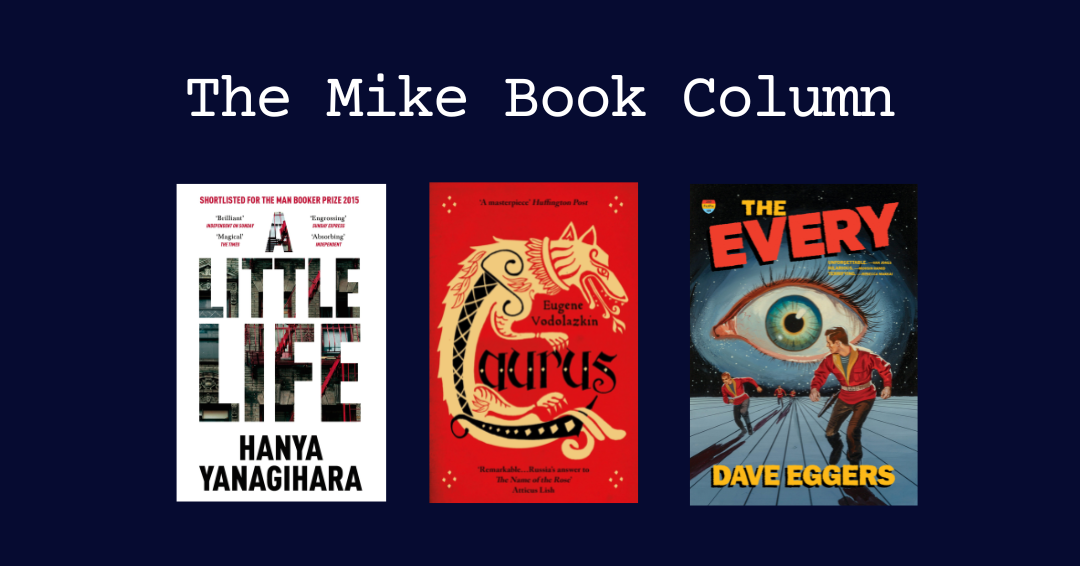

Photo Credit: Julliana Santos, Managing Editor

The Every – by Dave Eggers

Agata Mociani, Associate Arts Editor

What would happen if the world’s most powerful corporations eviscerated all of our remaining privacy through digital surveillance? The Every seeks to answer this question while exploring how various aspects of our tech-reliant, capitalist society intersect to pose an inescapable threat to our freedom.

The novel begins after a company called the Every buys all of the world’s top corporations, securing unlimited societal influence. Like a more advanced, contemporary iteration of Orwell’s Big Brother, the omniscient monopoly monitors citizens’ every move and bleeds into every aspect of their lives. When we first meet our protagonist, Delaney Wells, she is preparing for a job interview at the Every. Within the first few chapters, it is revealed that Delaney intends to dismantle the establishment from within. In a conversation with her roommate, she outlines her plan, declaring: “We inject the place with poisonous ideas, the Every adopts them, promotes them, and pushes them into the collective bloodstream of the world’s people” (166). Humouring her drug-related metaphor, her friend quips that the masses will ‘overdose.’ As Delaney’s plan comes to fruition, she discovers that, as with any addiction, digital overdose does not always lead to recovery.

Though the book’s premise is culturally relevant, the story itself is heavy-handed in its warnings about the Internet. The lack of subtlety feels almost condescending to the reader’s intelligence. For example, once Delaney is hired at the Every, Eggers uses the character’s newcomer status as an excuse to embark on a long tour of the corporation’s departments. Each branch that Delaney visits serves as a backdrop for the author’s stilted, didactic rants about topics he could not naturally integrate into the text.

The cast of The Every is unremarkable: for all its diversity, the characters blend together. Delaney’s coworkers lack depth, making it challenging for the reader to care about their fates. It is unclear whether the characters are underdeveloped due to lazy writing or because Eggers wants the reader to know that humans cannot exist as multifaceted beings in a post-privacy world. Regardless, their lack of substance detracts from the story. Like Winston in George Orwell’s 1984, Delaney symbolizes the concept of resistance, which prevents her from existing as a fleshed-out individual. After following Delaney for 575 pages, the reader is told that, “No one seemed to know Delaney Wells or would miss her,” and I am inclined to agree.

This is where one of the novel’s greatest narrative weaknesses lies: for the warning to be effective, we should feel compelled to care about what happens to the cast of The Every. Authors of dystopia should strive to humanize their characters, including those who are cogs in the machine of capitalism. If the reader cannot root for ordinary people enslaved by a surveillance state, how can they draw connections between their own experiences and those of the dramatis personae?

All in all, The Every is a well-researched treatise on the consequences of tech dependency, but it’s a manifesto, not a quality piece of dystopian fiction.

Laurus – by Eugene Vodolazkin

Aramayah Ocol, Contributor

Why are names important? What do names mark as we pass through different periods? In Laurus, Eugene Vodolazkin is keenly aware of how the bestowment of a name can mark and define a period. He relates this concept to the act of journeying and the metamorphosis that occurs along the way.

Divided into four parts, Laurus follows the life of Arseny, a man that begins as a peasant with healing abilities. However, everything valuable to him is quickly lost when disaster strikes. He is left alone and in isolation from the rest of society. Arseny renounces the world, leaving his small home in the woods.

Here, he enters a state uncommon to his world, but even more so to the modern understanding of our world. Eugene Vodolazkin challenges the concept of insanity through the idea of the Russian Holy Fool. Giving up everything he has and his secular life, Arseny lives off the charity of the village residents he travels by. His actions become counterintuitive: when and if he says things, they are things that wouldn’t be readily admitted, and he performs acts of charity detrimental to himself.

Arseny’s unstructured life as a vagabond and a Holy Fool shifts. He re-enters a state of being that becomes more articulate. Happening upon a monastery, Arseny enters into a rhythmic and religious lifestyle. Where previously Arseny’s actions had a paradoxical nature, here at the monastery he has the opportunity to reflect on the tragedies that catalyzed his itinerant life.

With a holistic view of his past leading up to this point, Arseny, now an old man, can move forward understanding the value of true sacrifice and love. Insanity and reason converge together and are balanced by the end of the novel.

A Little Life – by Hanya Yanagihara

Ridhi Balani, Contributor

I picked up this novel because the internet told me it would make me cry. That was true. A Little Life is a dynamic novel, which begins by introducing four college friends with different pasts and passions. There is Willem, an aspiring actor who works at a restaurant; Malcolm, who comes from a wealthy family, is confused about his life, and questions if architecture would satisfy his family; JB, a self-assured, aspiring artist who knows he will make his mark on the world; and Jude, with a mysterious past, working to become a lawyer. The story primarily revolves around Jude’s life and how it brings these friends and others together throughout his life as more and more of his past is revealed.

Yanagihara is so successful in writing characters in a way that makes you understand them and get attached very fast. Like people, there are so many multidimensional layers to the novel as it explores trauma, relationships, sexuality, purpose, abuse, culture etc. However, the most refreshing thing about the novel is how it explores relationships: those with friends, those with romantic partners, and those with parental figures. The novel shows how different parental figures can fail, as well as how they can succeed. Romantic relationships and their implications are also examined in terms of how abusive relationships can form, what the expectations of a romantic relationship are, and what it takes for them to persist or go wrong. The depiction of friendship, what it means, and how it changes throughout a lifetime is a particularly interesting point in the novel. The author explores what lies at the base of any relationship. How does one get into a position of forming them and how do they develop and persist or die out? How does one’s past impact how one goes on to live and form relationships? These are some of the questions that the novel tries to answer.

I would recommend this novel to anyone who likes to overthink things, like what life truly means. Or, to anyone who likes to read books that traumatize them. A Little Life is a dark, but also raw depiction of the life of the people in it, and will deliver on both those fronts.

(trigger warnings should be noted)