“Mystical Landscapes” at the AGO

Laina Southgate – CONTRIBUTOR

An audio-visual projection of forests, water, Aurora Borealis and The Cosmos sets the stage for the art exhibit “Mystical Landscapes: Masterpieces from Monet, Van Gogh & More” at the AGO, which is here until January 29, 2016. The overall theme of the exhibit is to convey how divinity and mysticism inform an artist’s interpretation of the natural world, in addition to how themes of turmoil can reflect and alter how an artist expresses spirituality.

The first portion of the exhibit – “Nature and Mysticism” – focuses on the ways in which nature and divinity intersect to create a space that is inhabited by themes of solitude and self-reflection. Paul érusier’s “Incantations in the Sacred Wood”, is an example of the mystical elements of nature because in the foreground is a group of women performing a spiritual ritual in the heart of the forest. The colours are subdued browns, greens, and reds, and one woman is kneeling before a small flame, holding a bowl. The proximity of the trees coupled with relative solitude of the procedure bonds together nature and the sacred, which creates an intimate and personal atmosphere. Another painting of note is Paul Gauguin’s “Yellow Christ”, which is a vibrant portrayal of Christ’s crucifixion. He is yellow, and the female onlookers are in modest blue gowns. In the background are rolling hills, red trees, and yellow grass which is the same colour as Christ. The use of colour in this painting is significant because instead of conveying a sombre and contemplative representation of Christ, it instead connects Him to the natural realm. Nature and mysticism converge in Gauguin’s painting which exemplifies the ways in which religion inspires artistic expression. The exhibit carries on past Monet and his famous “Water Lilies” to the subtle landscapes of Charles-Marie Dulac. The delicate portraits of brooding seas and contemplative deserts are nearly devoid of human life, and instead focuses on the use of light to convey the holy presence of God in nature.

The fourth portion of the exhibit – “Nocturnes and the Divine Darkness” – experiences a notable shift in tone as the paintings are deeper in colour and less explicit with the presence of the divine. ugène Jansson’s painting “Dawn over Riddarfjarden” is a cityscape which uses shades of blue and minimal red to convey a more serious mood. The city hints at human life, and the use of white swirls on the bottom on the canvas represent the presence of God. It is at this point in the exhibit that there is a divide between the first and second halves because “Landscape and the Dark Night of the Soul” features post World War One paintings that demonstrate the ways in which land serves as a medium to express social upheaval. The colours are black, brown and grey and the overall impression of this section is that of despair. There is no optimistic hint of the divine in the paintings, and the viewer is left feeling sombre and contemplative.

“The Wilderness and Spiritual Encounter” is the portion of the exhibit that demonstrates the ways in which the First World War affected how artists engage and seek representations of spirituality. Instead of explicit imagery of God, now divine inspiration is subtler. Emily Carr’s “Indian Church” is a good example of this, because while in the foreground there is a white church, the entire background is filled with forest. The viewer cannot see the sky, and the church is dwarfed by trees and wilderness. This serves to represent the ways in which nature is itself a form of spirituality, and the church is merely a representation of what can be found in the natural world.

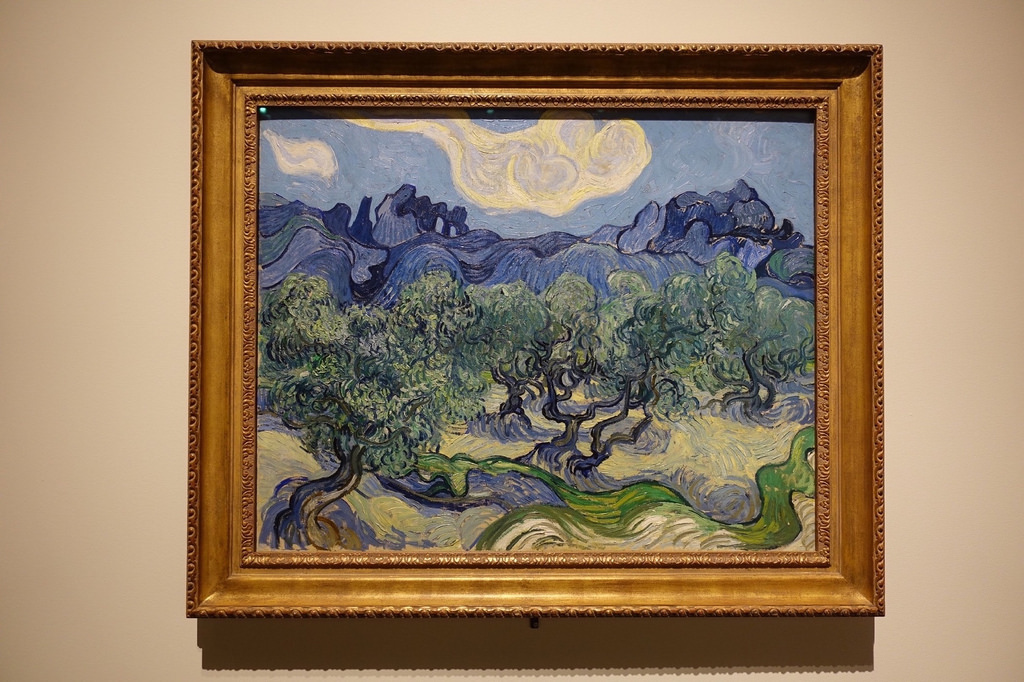

The final, and in my opinion, most notable portion of the exhibit takes the viewer away from the earthly realm and transports them to the cosmos. Engaging with themes of solitude, mystery, and divinity this section of the exhibit is the summation of the progression of art that has been experienced thus far. Positioned facing each other but on opposite ends of the room are Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” and Wenzel Hablik’s “Sternenhimmel.” Both depict space and stars, and yet they represent the two realities of artistic expression: where Van Gogh places the viewer on earth looking up at the stars, Hablik places the viewer literally in the stars. Two experiences of nature and the divine collide in these paintings, because in both the idea of the cosmos transcends and ultimately becomes an expression of God.

Throughout the exhibit, artists ask the viewer to consider the role that religion and nature play when experiencing a painting. Can one exist without the other? While a painting may not be explicitly engaging with religion, the landscape serves as the expression of the artist beliefs as well as the political climate in which they were painting. Organized to represent artists from Europe, Scandinavia and North America in addition to the progression of the relationship between the corporeal and celestial realms, “Mystical Landscapes: Masterpieces from Monet, Van Gogh & More” is not an exhibit that you want to miss.